Author: Bojidar Kolov | 01.04.2025

Picture: © Jo Kassis. Facade of Cibeles Palace with National Flags of Spain. Madrid, Comunidad de Madrid, Spain.

Few concepts have been as widely overused as ‘populism’. Employed as a heuristic device by political scientists or cast as a spell by pundits, used as a slur by mainstream politicians or as an unapologetic self-designation by their opponents, defined as a catch-all phrase by critics or as a precise analytical category by apologetic theorists, ‘populism’ is, at any rate, a staple of contemporary political discourse in all its shapes and forms. Despite the drastic divergences in the application of this essentially contested concept, everyone agrees that populism has something to do with ‘the people’. However, ‘the people’ is also ‘one of the least precise and most promiscuous of concepts’, as the English political theorist Margaret Canovan argues. Furthermore, she insists that ‘the people’ is to be regarded as a ‘quintessentially political concept’, i.e., a signifier that reveals the speaker’s political position, identity, and values, rather than a self-evident category. Thus, the popular signifier emerges as a nodal point of various discursive struggles aiming to fix divergent sociopolitical norms, identities, and subjectivities.

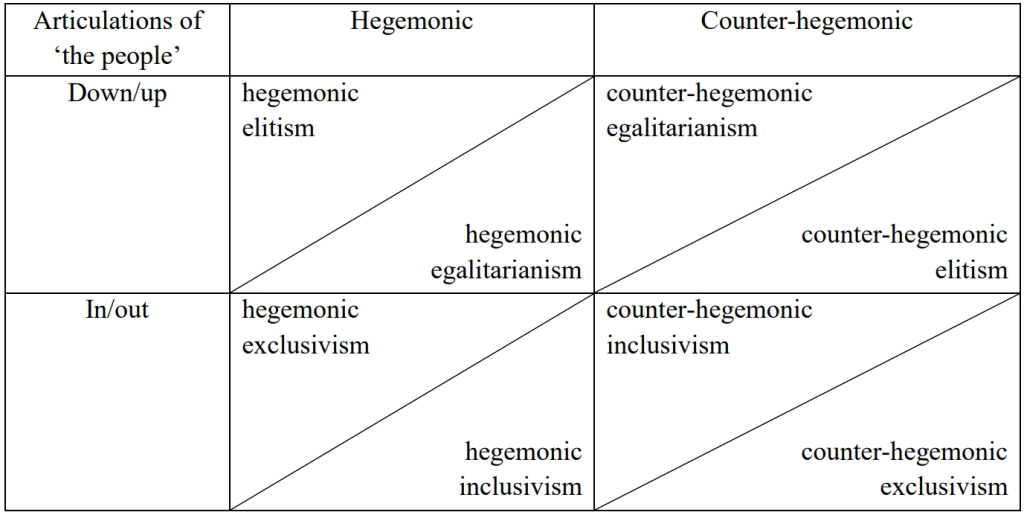

In this post, I will present an analytical approach to political discourse that shifts the conceptual and methodological focus away from identifying ‘populism’ to scrutinising the concrete constructions of ‘the people’ in particular contexts. I will illustrate how this approach works by discussing two examples: the political debate on migration in Europe and the political theology of the Russian Orthodox Church. In an article on the ecclesiastical ‘populism’ in Russia, I devised a general typology of the articulatory practices invoking ‘the people’ in political discourse. The typology integrates, into a coherent classificatory framework, two analytical distinctions drawn within the discursive approach to populism that originated with Ernesto Laclau’s seminal book ‘On Populist Reason’. Let me outline these distinctions briefly:

The first distinction made by Laclau is between the disparate strategies employed by hegemonic and counter-hegemonic discourses. While the former seeks to preserve and/or expand an existing socio-symbolic order by representing it as natural/virtuous/effective, the latter revolves around antagonism between certain unsatisfied demands and unrecognised identities on the one hand and the system that failed them on the other.

The second distinction drawn by Benjamin De Cleen and Yannis Stavrakakis concerns the different modes in which ‘the people’ and its other(s) are juxtaposed. ‘The people’ can be articulated horizontally along an in/out axis as a limited community (a nation, civilisation, religious community, etc.) distinguished from other such limited communities. In this case, the popular – or any collective signifier for that matter – acquires either inclusionary or exclusionary meaning in its particular discursive context. Alternatively, ‘the people’ can be articulated vertically along the down/up axis as an underdog (the working class, the ‘multitude’, ‘the 99%’, etc.) versus a small and illegitimately powerful group (‘the establishment’, ‘the elites’, etc.). That would be the egalitarian articulation of ‘the people’. Along the vertical axis, however, ‘the people’ can also be articulated as ‘the ignorant masses’, ‘the mob’, or simply as the ‘hard-working, law-abiding citizens’ who don’t challenge the established power relations in society. That would be the elitist articulation of ‘the people’. The distinction between the vertical and the horizontal axes is, of course, an analytical construction. In practice, these two modes of articulating collective identities often intertwine.

Combining the distinctions between the different strategies and modes of articulating ‘the people’, we arrive at the following schema, which displays how the down/up and in/out articulations transform as a result of their standing vis-à-vis a respective hegemonic order.

An important caveat here is that ‘hegemonic order’ should not be regarded as an objective given. Hegemony – and any social reality for that matter – is not immediately and transparently accessible: it is invariably constructed, perceived, imagined, and reproduced through symbolic representations, which are inevitably selective, contingent, and political.

In that sense, the above typology can be used for both contextualising self-interpretations and analytical characterisations. To illustrate this point, let us take the well-known example of the ‘refugees welcome’ discourse. Looked at from the perspective of its promoters, ‘the refugees welcome’ campaign falls under the category of a counter-hegemonic inclusivist project struggling against the exclusivist ‘fortress Europe’ hegemony. Here, the refugees are simultaneously a horizontal ‘other’ (as ‘they’ come from the outside) and an underdog. While the ‘refugees welcome’ discourse does not articulate the asylum seekers as ‘the people’, it challenges exclusionary constructions of the (ethnic/national/European) ‘us’ in favour of more universal signifiers such as ‘humanity’.

However, depending on the analyst’s research question and positionality, the ‘refugees welcome’ discourse could be characterised as part of a larger exclusionary hegemonic order because it does not challenge (enough) the ‘new global apartheid’, defined as a system of exclusionary and hierarchical citizenship and militarised border regimes. Here, the people-as-an-underdog are not only the ones forced from their homes by conflict or persecution, but also the disadvantaged citizens/stateless people of the Global South as a whole.

In turn, a typical right-wing ‘populist’ anti-immigration discourse, in the self-interpretation of its exponents, would be opposed to the ‘liberal and multiculturalist’ inclusivist hegemony in Western Europe. However, some anti-immigrant positions can be categorised – at least theoretically – as conducive to the supposed inclusivist hegemony because they oppose only ‘illegal immigration’ and are not against ‘documented refugees’ and ‘high-value migrants’. Thus, the articulation of ‘the people’ in anti-immigration discourses can range from horizontal exclusivism (nativism in favour of ‘our people’) to vertical elitism (meritocracy in favour of ‘the hard-working and talented people’) and is often a combination of both.

In principle, a single political discourse could combine all variants listed in the schema in all possible ways when articulating ‘the people’ differently on different terrains or scales as we see with the Russian Orthodox Church. Its civilisational articulation of ‘the people’ can be characterised as hegemonically inclusive vis-à-vis Belarusians and Ukrainians, because it bluntly represents them as ‘sub-ethnicities’ of the ‘triune Russian people’. At the same time, the ecclesiastical leadership promotes what it sees as counter-hegemonic egalitarianism, advocating for inter-civilisational equality as opposed to Western unipolarity and ‘civilisational expansionism’.

On the terrain of the Russian Federation, however, church officials endorse the national elite’s hegemony (of which they are part) by normalising the power relations established in the country since the 1990s. The Russian Orthodox Church portrays itself as ‘the church of the poor’, yet it systematically undermines the agency of the very disadvantaged groups it claims to support. Meanwhile, it reserves sociopolitical power for itself, the state, and economic elites as the true providers of ‘the people’s needs’. Furthermore, the official church has been at the forefront of solidifying the hierarchical and exclusive multiculturalism established in the country in the last decades. With the Slavic Orthodox culture at the top, the other ‘traditional religions’ underneath, and the ‘non-traditional’ cultural-religious communities stripped of any recognition, this system is still narrated by the Russian elites as an alternative global model to Western ‘aggressive secularism’ which allegedly marginalises all religions.

These examples demonstrate the capacity of the typology to grasp complex political discourses that defy simplistic characterisations. Indeed, analysing ‘populist’ discourses requires breaking them down into specific articulations of ‘the people’. Thus, by examining the strategies, modes, and scales of articulating signifiers of collective identity, we can better characterise the political actors’ self-interpretations and engage in a more comprehensive analysis of their discourses.

Finally, this analytical approach foregrounds the key methodological role of posing precise research questions and making one’s positionality clear. In that sense, reflecting openly on how we construct our objects of analysis and why we want to know what we want to know about them is as essential as our methodological transparency.

Author

Bojidar Kolov is a member of the international research project ‘Values-Based Regime Legitimation in Russia’ at the University of Oslo, Norway. Recently, Kolov defended his doctoral dissertation on the contemporary political theology of the Russian Orthodox Church as part of this project. In addition to his PhD, he holds an MA in EU-Russia Studies from the University of Tartu in Estonia and a BA in Political Science from Sofia University in Bulgaria. Kolov also studied Theology at the Department of Eastern Christian Studies at the Stockholm School of Theology. His research focuses on church-state relations, religious nationalism, and postsecularism.

Bojidar Kolov is a member of the international research project ‘Values-Based Regime Legitimation in Russia’ at the University of Oslo, Norway. Recently, Kolov defended his doctoral dissertation on the contemporary political theology of the Russian Orthodox Church as part of this project. In addition to his PhD, he holds an MA in EU-Russia Studies from the University of Tartu in Estonia and a BA in Political Science from Sofia University in Bulgaria. Kolov also studied Theology at the Department of Eastern Christian Studies at the Stockholm School of Theology. His research focuses on church-state relations, religious nationalism, and postsecularism.

Citation: Kolov, Bojidar, Constructing ‘the People’: Logics, Modes, Terrains, KonKoop DataLab Blog, published online: 01/04/2025, https://konkoop.de/index.php/blog/datalab-blog-constructing-the-people-logics-modes-terrains/