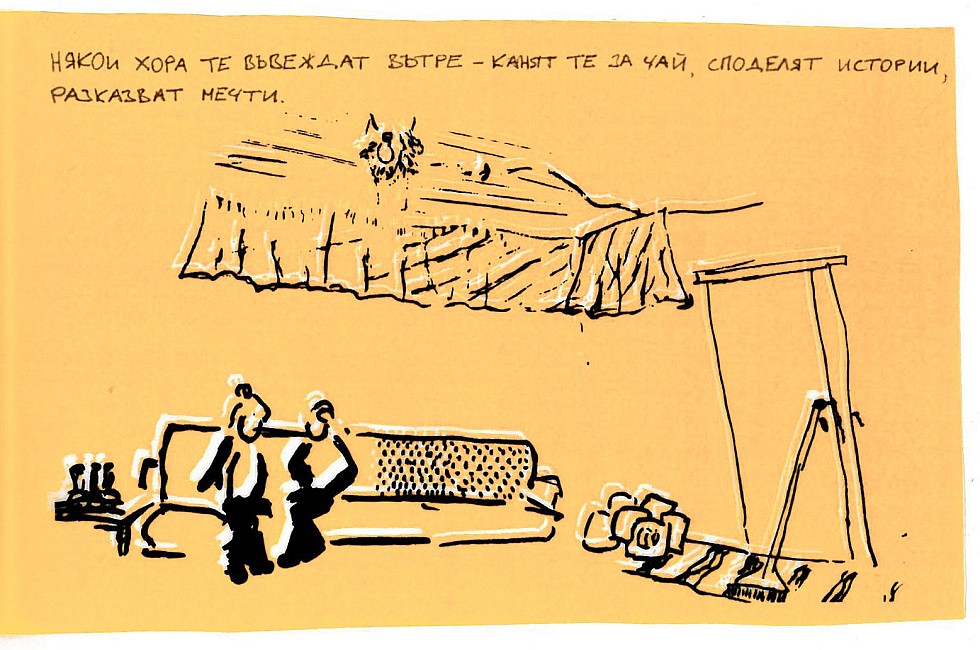

Picture: Drawing from the “Beauty We Share” project, Stolipinovo, 2019 (c) Duvar Kolektiv

How can anthropological research produced for Western markets of academic knowledge become more relevant to or even benefit the people and societies studied? Here I will discuss a previously proposed solution: ‘stealing time’ from one’s institutional arrangements for other, locally situated forms of commitment alongside one’s research work. I base my reflections on fieldwork in Stolipinovo, a large urban district in Plovdiv, Bulgaria, which has long been stigmatised as a ‘Gypsy’ or ‘Roma’ neighbourhood, and suffers from high-levels of antigypsyism even though most of Stolipinovo’s residents identify as Turkish, a remnant of the 500-year incorporation of my home town Plovdiv into the Ottoman Empire. In the fieldwork I have carried out there with others since 2015, I have been particularly interested in how we can challenge both everyday and institutional racism not only through scholarship but also through more direct forms of engagement.

Challenging the Western matrix of knowledge production

As a Georgian who did her PhD in a Western institution, Lela Rekhviashvili writes about how her research participants – street traders subject to state repression in Georgia –always asked her whether her project would benefit them at all. After her fieldwork, she felt that her research ethics had been compromised by the power of her Western academic context to discipline her into producing knowledge that only fit Western theories and concepts and was thus irrelevant to the research context and the people whose intimate knowledge and experiences she was seeking. Lela and her co-authors’ proposal for making up for this is, whenever possible, to steal time from the exigencies of academia:

By ‘stealing’ time: to spend it with research participants before and after data collection; to contribute to spaces of knowledge production which will not be counted in our formal performance; by attempting to make our research questions more relevant to local political contexts; by utilising our access to transnational academic space to bring up overlooked problems, concepts and challenges; and by sharing our privileged access to the resources of Western academia.’ (p.108)

This is about confronting the inherent coloniality of international knowledge production by opening breaches in its largely metropolitan intellectual projects (akin to producing ‘theory from the South’, but from recesses not yet recognised for their theoretical and ideological potential, such as Global East). It is also about something that other Eastern European scholars working from the West have termed the reproductive work (or kitchen-work) of social research.

In my own case, this ‘reproductive work’ has meant maintaining relationships with my interlocutors beyond the remit of research projects, building real friendships, and striving to strike a balance between ‘taking from’ them (information, stories, and experiences, moreover benefitting from their extended hospitality and emotional investment) and ‘giving back’, which has meant not only trying to translate the meanings and the (usually minimal) wider effects of my research for my research participants, but also getting involved in issues important to them and helping out with my intellectual resources or cultural capital (despite the inherent risks and failures entailed in such commitments). Then, the desire to grow my involvement beyond the personal (whilst continuing to invest in it) was what motivated me to pursue larger and better supported forms of engagement, such as the founding of an arts collective. Since I was a precarious scholar myself, lacking the backing of an institution or employment for extended periods of time, stealing time was not always relevant to my situation. Another strategy – combining time – became important here. Combining time is about seeking avenues for fieldwork and gathering ethnographic data while doing something else, such as an artistic project or field interviews for German academics from the Ruhr.

Stealing and combining time for Stolipinovo

In 2018, Hannah Rose, an artist from the UK, and I began a series of small collaborative artistic/culture-focused projects in one of the most deprived parts of Stolipinovo, facilitating processes of low-key co-creating and mutual learning. We were able to secure small funding on an on-and-off basis. A year later, we defined our experiments as an ‘arts collective’, which also included Yanka Simova, our closest partner in the area, whose welcoming and curiosity toward us had been invaluable. We chose the name Duvar Kolektiv – ‘duvar’ means ‘wall’ in both Turkish and Bulgarian – referencing our main goal to work against the walls of social segregation surrounding Stolipinovo.

As guests in our hosts’ humble homes, we spent months discussing beauty and each other’s different worlds and experiences with the aim of gradually fostering confidence and hope among the families we worked with. Exhibiting co-produced artwork in Plovdiv art spaces was an important stage in the process. Our collaborators rarely dare to leave Stolipinovo or have a chance to meet non-racist outsiders, so we organised exhibition openings as occasions for them and friendly, open-minded Bulgarian audiences to encounter one another (the meetings were transformative for both sides). One of the exhibitions is also available online, showcasing the fashion design talent of Yanka and another local woman.

During the pandemic lockdowns, we had the chance to support a group of aspiring grassroots activists, helping them establish an online community media named Filibeliler (‘Plovdiv People’ in Turkish). At the same time, we became involved in the long-term political, media and legal struggles of the group against institutional racism and the subpar urban services provided in the district. We also collaborated with Stolipinovo residents on cultural projects: realising a documentary film by Osman Yuseinov titled ‘Inherited Crafts’, about the life and work of craftspeople in the neighbourhood, and Abdulsamed Veli’s proposal for ‘The Voice of Stolipinovo’ community singing contest. The four-month-long contest and online show was so embedded in the community dynamics that we still don’t have anything viewable for outside audiences.

Since 2022 we have scaled down our time ‘with’ Stolipinovo as I try to catch up with my academic writing and publishing and Hannah pursues her education as an art psychotherapist. In 2023, however, I had the opportunity to turn an invitation for an academic publication into a paper also aimed at a general Bulgarian audience (combining time again). I took advantage of the journal’s open-access online format to experiment with producing a multimedia-rich paper with a thriller-like plot and non-scholarly presentation of the sociological analysis (“Stolipinovo: Trash, Media, Government, Racialisation”). The paper turned out to be both engaging and transformative for the average non-academic reader. In fact, the journal subsequently invited us to submit an additional ‘artistic’ contribution and the full team of Duvar Kolektiv – Hannah, Yanka and myself – worked on a collaborative biographical-reflexive essay (“Duvar Kolektiv: Journeys Towards the Discarded”).

Through these creative endeavours I have attempted to relate scholarly work to meaningful contributions to the Stolipinovo community and the wider Bulgarian society. Other dreams are as yet unrealised, such as Abdulsamed’s vision of a neighbourhood museum and my parallel hope for collating an oral history of Stolipinovo. We are just looking for the right combination of opportunities to arise. Combining time for anti-racist work that empowers people and restores their dignity while also reconfiguring the matrix of academic knowledge production remains a foremost concern.

Author

Nikola A. Venkov-Rose is interested in the politics of living together in the context of the Eastern European city and how people’s fates are affected by power inequalities and marginalisation, by racialisation, by the tussles of civil society, and by the domains of government, media, and professional expertise. Staying close to politics as an everyday practice suggests privileging ethnography as a method of data collection. He is also working with and elaborating further Ernesto Laclau’s post-foundational discourse theory. Nikola is an assistant professor at the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences (since 2021). He holds a PhD in Sociology from the University of Sofia (2017) and has been a fellow at the Centre for Advanced Study Sofia and the Leibnitz Institute for Regional Geography in Leipzig.

This contribution is based on a talk I delivered at The Common City Conference in Uppsala, Sweden in 2024.

> Nikola A. Venkov-Rose’s homepage at Bulgarian Academy of Sciences