In:Security Report Series

In:Security Report Series

Image: Abandoned Border (c) pixabay/ Tama66

Old Fears and New Threats:

Insecurity and Societal Cohesion in Russia’s Neighbourhood

CONTENTS

North Eastern Europe: Poland and Finland

Paramilitary civil society – remaking defence from below in Poland

Finnish security perceptions and the securitisation of borders with Russia

Russia’s immediate neighbourhood: Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus

Weaponisation and its reverse: Implications for Ukraine’s security

Moldova’s National Security Strategy and societal cohesion

Divided Belarusian society and the potential consequences of emerging insecurities

South Caucasus: Georgia and Armenia

The Influx of Russian migrants to Georgia – a factor of insecurity?

Armenia’s Post-War Security Conundrum: Contemplations after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

Publication date: May 17th, 2024

Citation: Nadja Douglas, Weronika Grzebalska, Kornely Kakachia, Andrei Kazakevich, Asbed Kotchikian, Yuliia Kurnyshova, Sabine von Löwis, Inna Șupac and Joni Virkkunen, Old Fears and New Threats: Insecurity and Societal Cohesion in Russia’s Neighbourhood, KonKoop In:Security Report 1/2024

The KonKoop topic line ‘In:Security’ focuses on security ‘from below’, paying particular attention to societal perceptions of insecurity.

[1] For more about the topic line ‘In:Security’: Link to topic line description.

[2] Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1998).

[3] Graeme P. Herd and Joan Löfgren, ‘“Societal Security”, the Baltic States and EU Integration’. Cooperation and Conflict, 36(3), (2001).

[4] Barry Buzan, People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-cold War Era (Colchester: ECPR Press, 2007).

[5] Ronald F. Inglehart and Pippa Norris, ‘The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Understanding Human Security’, Scandinavian Political Studies 35 (1), (2012).

[6] Nick Vaughan-Willams (2021), Vernacular Border Security: Citizens’ Narratives of Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

Vernacular security theories treat security as a socially/locally situated practice and thus emphasise the societal dynamics often overlooked by traditional security discourses.

[7] Nils Bubandt, ‘Vernacular Security: The Politics of Feeling Safe in Global, National and Local Worlds’, Security Dialogue 36(3), (2005).

[8] Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity (Cambridge: Polity, 1991) quoted in Bubandt 2005.

Borders are places of counter-imagination and practices that cut across state-driven dividing lines.

[9] Lee Jarvis and Michael Lister, ‘Vernacular Securities and their Study: A Qualitative Analysis and Research Agenda’, International Relations 27(2), (2013).

[10] Robert Cooper, The Breaking of Nations: Order and Chaos in the Twenty-First Century (London: Atlantic Books, 2004).

If the 2014 annexation of Crimea was a turning point for Polish defence policy, Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine marked an epochal shift.

[15] Łukasz Dryblak, ‘Organizacje proobronne a państwo polskie 1989–2015’, in Organizacje Proobronne w Systemie Bezpieczeństwa Państwa, edited by Paweł Soloch et al. (Warsaw: Instytut Sobieskiego, 2015: 20–32).

[16] Matej Kandrik, The Challenge of Paramilitarism in Central and Eastern Europe (Berlin: German Marshall Fund of the US, 2020).

[17] Linda Hart, ‘Willing, Caring and Capable: Gendered Ideals of Vernacular Preparedness in Finland’, Social Politics Vol. 29, Issue 2, (2022).

[18] Interview conducted on 1 Dec 2016 as part of PhD research.

[19] GLOBSEC Trends 2023: United we (still) stand (Bratislava, 2023), Link

[20] War Studies University, Stosunek Polaków do obrony Ojczyzny [Attitudes of Poles towards Defence] (Warsaw, 2022).

[21] Warsaw Enterprise Institute, Poland Ready for the Crisis? (Warsaw, 2022), results vary across surveys depending on the exact wording of the question, Link

It has become clear to Finland that Russia is also exercising hybrid warfare in its confrontation with the West.

[22] Government of Finland, Valtioneuvoston päätös rajanylityspaikkojen väliaikaisesta sulkemisesta ja kansainvälisen suojelun hakemisen keskittämisestä. [Government Decision on the temporary closure of border crossing points and the centralisation of applications for international protection], 11.1.2024, Link

[23] Heini Larros and Sami Metelinen, ‘Suomalaiset liittyvät Natoon yhtenäisinä’ [Finns Join Nato as One], Finnish Business and Policy Forum EVA, 23 November 2022, Link

[24] Tolkki Kristiina, ‘Vahva enemmistö tukee Suomen Nato-jäsenyyttä’ [Strong Majority Supports Finland’s Membership of NATO], YLE, 21.12.2023, Link; S.M. Amadae, Hanna Wass, Jari Eloranta, et al., Guarantees for Multifold Security Concerns: Finns’ Expectations for Security and Defence Policy in the Lead-Up to the 2024 Presidential Elections, NATOpoll Policy Brief 2/2023, Link

[25] ibid.

Despite strong public and political demand for a border barrier fence, it is openly acknowledged that it is merely symbolic.

[29] See, for example, Jussi Laine in Iida Hallikainen, ‘Professorilta ankaraa kritiikkiä Marinille itärajan aidasta: “Hanke on järjetön” [Professor harshly criticises Marin on eastern border fence: ‘The project is absurd’], Iltasanomat, 19.10.2022, Link; Johanna Laakkonen and Sampo Vaarakallio, ‘Aita ei estä rajan ylitystä, se vain tekee siitä vaarallista – Suomen miljoonahankkeesta voi olla enemmän haittaa kuin hyötyä’ [A fence doesn’t stop you crossing the border, it just makes it dangerous – Finland’s multi-million project could do more harm than good], YLE, 19 October 2022, Link

[30] See, for example, Amnesty International, ‘Hallitus jätti portin auki uudelle täyssululle – Amnestyn huomioita itärajasta’ [The government left the door open for a new full closure – Amnesty’s comments on the eastern border]. 13.12.2023. Link; Olga Davydova and Pirjo Pöllänen, ‘Itärajan sulkemisesta käytävä keskustelu sivuuttaa ylirajaisuuden’ [The debate on closing the eastern border ignores transnationalism], Politiikasta.fi, 4.12.2023. Link; Fatim Diarra, ‘Itäraja, ihmisoikeudet ja Venäjän törkeät temput’ [The eastern border, human rights and Russia’s outrageous antics], Blog post, 15.11.2023; Mikael Kaivanto, ‘Asiantuntija lataa suorat sanat ministerin lausunnolle rajatilanteen uhkakuvasta: “Perusteetonta”’ [Expert blasts minister’s statement on border threat: ‘Unjustified’]. Iltalehti, 10.12.2023, Link; Saara Hirvonen, ‘Kuinka paljon turvapaikanhakua voi rajoittaa? Kaksi asiantuntijaa kertoo näkemyksensä’ [How much can asylum applications be restricted? Two experts give their views], YLE, 22.11.2023, Link

[31] Viivi Salminen, ‘Oikeuskansleri rajasulun jatkosta: Sisäministeriön selvitettävä pian myös muita vaihtoehtoja’ [Chancellor of Justice on the continuation of the border barrier: the Ministry of the Interior must soon also examine other options], Helsingin Sanomat, 1.1.2024. Link; Mikko Pesonen, ‘Laillisuusvalvoja vaati useita muutoksia myös uusimpaan rajapäätökseen’ [The Legal Ombudsman also requested several changes to the latest border decision], YLE, 29.11.2023, Link

[32] Finnish Border Guard, ‘Rajan ylittäminen polkupyörällä ei ole sallittua Kaakkois-Suomen rajanylityspaikkojen kautta 9.11. alkaen’ [Crossing the border by bicycle is not allowed via border crossing points in South-East Finland from 9.11], 13 November 2023, Link

Traditionally non-military spheres have become part and parcel of military warfare.

Some EU and NATO member states prefer to act in their own economic interests rather than within the framework of (counter-) weaponisation.

The Strategy does not address the most significant risks to Moldovan national security: the lack of social cohesion and a national consensus on the accession of Moldova to the EU.

[37] Important note: The data used in all the figures are only valid for the right bank of Dniester River (excluding Transnistria).

An inclusive dialogue with different parts of Moldovan society with a view to achieving a national compromise on EU accession may foster social cohesion.

The most tangible consequence of ignoring public opinion is out-migration, which was never higher in the entire history of independent Belarus.

The most visible threat to regional security stems from the ability of the Belarusian defence industry to help rebuild Russia’s military capabilities.

[38] Kornely Kakachia and Salome Kandelaki, ‘The Russian Migration to Georgia: Threats or Opportunities’, 19.12.2022, PONARS Eurasia, Link

[39] Margarita Zavadskaya, ‘The War-Induced Exodus from Russia: A Security Problem or a Convenient Political Bogey?’, 29.03.2023, Finnish Institute of International Affairs, Link

[42] Kakachia & Kandelaki, 2022.

Some view the presence of Russian migrants as an economic benefit, while others perceive it as a security and political risk.

[43] The State Commission on Migration Issues has published a list of countries whose citizens can travel visa-free to Georgia and stay for one year at: Link

[44] As the prime minister stated, one million ethnic Georgians reside in Russia and therefore ‘to have direct flights with Russia is very normal’, adding that ‘this does not mean that we are engaged in some kind of political consultations with Russia’. He also emphasised that the new direct flights would facilitate the establishment of trade and economic links with Russia. Source: Civil.ge, ‘PM Garibashvili: We Would Destroy Georgia’s Economy If We Imposed Economic Sanctions on Russia’, Civil Georgia, 24 May 2023, Link

The high concentration of Russians in Georgia could make the country especially susceptible to Russian propaganda.

[48] Kakachia & Kandelaki, 2022.

Armenia’s straying from Moscow’s orbit is due more to the regime change in 2018 and overtures made by the new government to the West than to developments in Ukraine.

[50] Steven Levitsky and Lucan A. Way, ‘Elections Without Democracy: The Rise of Competitive Authoritarianism’, Journal of Democracy 13 no. 2, (April 2002): 51.

[51] For a more detailed discussion of Armenia-Russia relations after the Velvet Revolution, see Alexander Markarov and Vahe Davtyan, ‘Post-Velvet Revolution Armenia’s Foreign Policy Towards Russia’, Demokratizatsiya: The Journal of Post-Soviet Democratization 26, no. 4, (Fall 2018): 531.

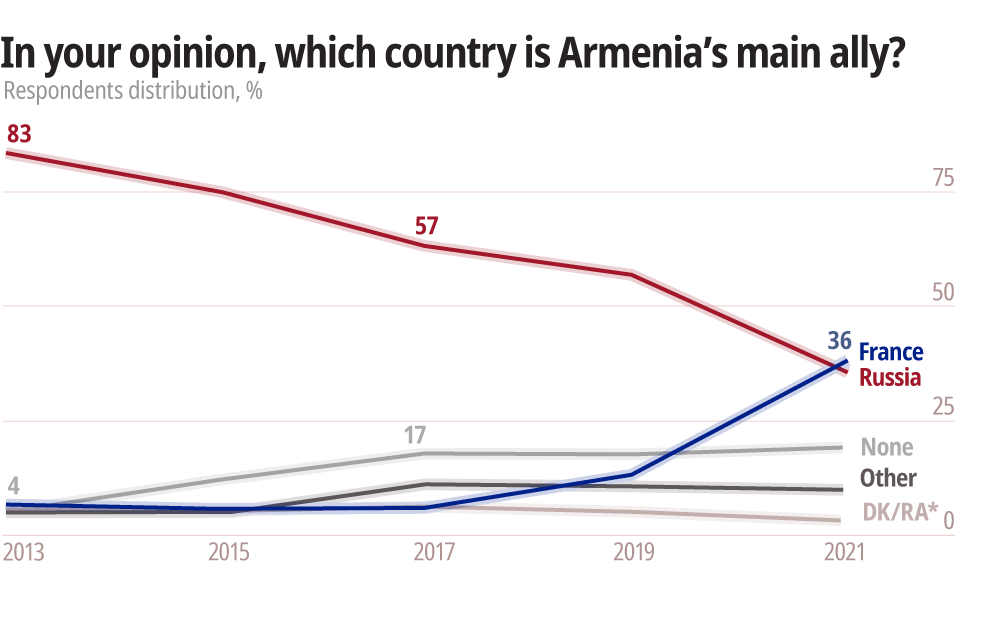

Various surveys show that fewer and fewer Armenians view Russia as a reliable partner.

[54] With a staff of just over 200, the EUMA has a stated mandate which by far exceeds its capacity and intent. Thus, other than monitoring the Armenia-Azerbaijan border, the EUMA is supposed to be ‘… contributing to build confidence between populations of both Armenia and Azerbaijan and, where possible, their authorities.’ Link

This ultimately calls into question the perception of Eastern Europe as one homogeneous geopolitical region and suggests taking a more disaggregated approach.

The dramatic images of Ukrainian society under attack have raised very practical questions on what citizens should do in case of an actual attack on their country.

Introduction

Nadja Douglas (editor) is a political scientist and researcher at ZOiS, currently coordinating the KonKoop topic line ‘In:Security in Eastern Europe’. She holds a master’s degree in International Relations from Sciences Po Paris and a PhD from Humboldt University Berlin.

Nadja Douglas (editor) is a political scientist and researcher at ZOiS, currently coordinating the KonKoop topic line ‘In:Security in Eastern Europe’. She holds a master’s degree in International Relations from Sciences Po Paris and a PhD from Humboldt University Berlin.

The full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 has had severe implications for security perceptions, discourses and internal societal dynamics, in particular in countries in the Russian Federation’s immediate vicinity. Viewed in terms of the ‘ontology of security’, the invasion was a paradigmatic rupture for the entire region, which as well as reinforcing longstanding fears, has given rise to new threats and insecurities. Countries in Russia’s neighbourhood have reacted differently to the new security context. However, there are also commonalities that this report seeks to carve out. In some states, societal cohesion and national unity have increased as a result of the war; in others, existing divisions have been aggravated and societies are polarised on the issue of the war itself or Russia more broadly.

In its search for new political strategies and a unified reaction to Russian aggression and the destabilisation of the European post-war security order, the prevailing international (Western) discourse has since February 2022 reverted mostly to classical security imaginaries of deterrence and rearmament, essentially a military-centred approach. In a similar vein, contemporary academic and policy-oriented literature is mostly focussed on state-centric policy debates and ‘top-down’ analyses of ‘hard security’ issues. By contrast, the KonKoop topic line ‘In:Security’[1] seeks to shift the focus towards understandings of security ‘from below’, paying particular attention to societal perceptions of insecurity. Since these perceptions of security are collective, constructed by individuals who see themselves as members of a community,[2] the concept of ‘societal security’ will play an important role here. The shared identity of those ‘security communities’ for whom the survival in the face of perceived (‘constructed’) threats is paramount can also transcend international borders. The greater the threat to the identity, the stronger the determination to preserve this identity.[3] At the individual level, a distinction can be made between objective and subjective security. The individual subjective feeling of safety ‘has no necessary connections of actually being safe’.[4] The label ‘subjective’ could even be misleading here, as the ‘security issue is not something individuals decide alone’ (Buzan et al. 1998). Nevertheless, it has repeatedly been stressed that changes to ‘subjective security’ can also determine changes in values within society[5] as well as the understanding of democracy.[6] The growing relevance of ‘ontological security’, seen in a shift from quantitative or physical accounts of ‘being secure’ towards qualitative accounts and societal efforts towards ‘feeling secure’ (Vaughan-Willams 2021), matters in this context.

This report is based on a workshop held at ZOiS on 6 June 2023 on the topic of “In: Security in Border Regions”, organised by Nadja Douglas and Sabine von Löwis. It brought together a diverse set of experts on international relations, border studies, and (critical) security studies from various countries in Eastern Europe and the South Caucasus. The workshop was the first in a series of workshops and publications within KonKoop’s topic line on In:Security, all of which will address the various dimensions of security and insecurity in the region.

In a nutshell, the aspiration of the workshop and the resulting report is to complement the prevailing ‘top-down’ analyses of state and government security practices with a ‘bottom-up’, actor-oriented and comparative perspective on how these practices are perceived as well as produced and reproduced. Another focus will be on the implications of security practices for ‘societal security’, recognising society as security’s main referent object.

Vernacular security theories are a good way to approach these issues, because they treat security as a socially/locally situated and discursively defined practice and thus emphasise the societal dynamics often overlooked by traditional security discourses. Security in the vernacular sense is a ‘political way of dealing with the ontological issue of uncertainty’.[7] It is open to comparison and grounded in specific contexts. The Polish case illustrates clearly how grassroots sentiments and actors, such as paramilitary civil society, have gained in relevance at the latest since 2014, contributing to the remaking of a new ‘security from below’ and the ultimately state-led comprehensive reform of Polish defence.

The situatedness of security and the significance of historical memory become apparent when looking at the Finnish population’s altered perception of security since February 2022. Finland’s policy towards Russia has changed from a neutral-pragmatic to an explicitly defensive-pragmatic one, driven by the population’s desire for more security and certainty. The people’s need for assurance about where Finland belongs, bearing in mind its historical experiences with Russia, was an important factor in the country’s decision to join NATO.

Security is thus a socially expressed practice, and different societies (or imagined communities) have different ways of socially producing, discursively portraying, and politically managing it.[8] The Ukrainian case certainly stands out here, given that the country is at the centre of the Russian war of aggression. Based on the Ukrainian experience, we show how the Russian logic of ‘a weaponisation of everything’ – an extension of war to non-military resources, such as energy, food and the environment – has not only created unprecedented chains of insecurity, but also led to Ukrainian society becoming more robust and resilient. The neighbouring societies of Moldova and Belarus have also been disproportionately affected by the Russian war, especially in terms of social and economic consequences. While their security situation is not comparable to Ukraine, many security risks are imminent and a constant burden for societies that have already had to shoulder longstanding insecurities emanating from a lack of societal cohesion and unity. Societal divisions have deepened, also with regard to Russia and the Russian war against Ukraine. Such polarisation makes those societies vulnerable to external interference.

This is an anxiety shared by Georgian society, which seeks to gain from but at the same time fears the consequences of an influx of Russian migrants. Here, there is the worry not only that Russia will drive a wedge into Georgian society from the outside, but also that Georgia’s democratic governance will be eroded from the inside. In a similar vein, Armenia is struggling with Russian interference and the resulting divisions within society. It has been more affected than other countries by Russia’s loss of regulatory power in the region. The current threat to the country’s democratic consolidation process and the stagnating normalisation process in its relations with Azerbaijan do not contribute to an enhanced perception of security either.

Another focus of the report is on borders and bordering as well their different meaning for security. On the one hand, the political border is a place of securitisation, which the state fortifies and militarises in order to guard against unwanted attacks or mobility across it. But borders are at the same time places of counter-imagination and practices that cut across the state-driven dividing lines, thus contributing to vernacular understandings of security and insecurity.

Political borders are very concrete, material structures that demarcate the territorial limits of states or transnational organisations like NATO, the EU, and the Schengen Area. They are governed by a border regime and regulations that define how to cross them (when, for whom, what and how). Yet they are at the same time very symbolic and constructed in the way the territories on either side are characterised, narrated and imagined. Beyond institutional frameworks, the vernacular sense of borders is important, i.e. how borders are practised on the ground by those managing them but also by those crossing and living close to them. In both ways borders may carry meanings of security and insecurity and expectations of more or less of it on the ‘other’ side.

Bordering – the understanding of borders as multi-dimensional practices – is also a social and cultural process that is not necessarily bound to territory and the concrete borderline on the ground. With the concept of borderscapes, the border is de-territorialised and brought into the realm of social, economic, cultural and political production and construction of inclusion and exclusion at different levels and places. This process of bordering is fluid and dislocated. It includes the state as well as individuals deconstructing and producing borders between what they perceive to be one’s own and what they perceive to be other.

This report aspires to engage with new ontological ideas about what it means to be safe, and covers a wide array of security challenges and risks that societies in the region face. For many of these societies, security has become not an end in itself, but rather a means and an ‘opportunity to choose to live otherwise’.[9] The bordering concept is helpful in approaching the dynamics within and between the states affected by Russia’s war against Ukraine since 2014, especially with regard to processes of belonging, migration and flight, discourses of fear and trust,and infrastructural coupling and decoupling. In this sense, we treat security as a fluid concept that ultimately opens up possibilities for societal emancipation not only from an ‘external threat’ but also in a transbordering sense from state-centred and sanctioned notions of security and insecurity.

North Eastern Europe: Poland and Finland

Paramilitary civil society – remaking defence from below in Poland

Weronika Grzebalska is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In the past, she was a RethinkCEE fellow of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a Trajectories of Change fellow of the ZEIT-Stiftung, a member of the FEPS Young Academics Network, and president of the Polish Gender Studies Association. > Homepage

Weronika Grzebalska is an Assistant Professor in Sociology at the Institute of Political Studies of the Polish Academy of Sciences. In the past, she was a RethinkCEE fellow of the German Marshall Fund of the United States, a Trajectories of Change fellow of the ZEIT-Stiftung, a member of the FEPS Young Academics Network, and president of the Polish Gender Studies Association. > Homepage

The 2014 and 2022 Russian military invasions of Ukraine were watershed moments for Polish security perceptions and policy, marking a shift from EU-backed softer and broader security conceptions towards more traditional and regional ways of thinking about defence. In brief, there has been a turn from seeing Russia as a ‘partner for peace’ to viewing it a threat to the liberal international order; from a professional, expeditionary model of the armed forces to territorial defence and deterrence; and from a post-militarist society towards one engaged in its own defence. Policy analyses tend to focus on state-level defence documents and reforms as a driving force behind the post-2014 Polish Zeitenwende. Employing a vernacular perspective, this chapter zooms in on the overlooked grassroots sentiments and actors – paramilitary civil society – which prepared the ground for the ongoing defence shift by remaking security from below.

Paradigm shifts in defence

After joining Western alliances around the turn of the century (NATO in 1999 and the EU in 2004), Poland began harmonising its security policy with that of its Western partners. At the time, ‘old Europe’ was embracing a more ‘postmodern’ security agenda that was critical of military might.[10] Apart from putting the Polish military under democratic control and international surveillance, the changes to Polish security policy led to the reduction and professionalisation of the army in line with NATO’s out-of-area crisis management goals, the suspension of conscription, and the gradual detachment of citizens from defence.

While accompanied by strong democratic support and hope in a Pax Europaea, these changes were also met with some ambivalence. Given Russia’s proximity, it was felt that Poland, like the Baltics, could not afford to fully let go of the ideals of sovereignty and deterrence. Still, Poland’s attempts to rebuild territorial formations were curbed by Western partners wary of isolating Russia, [11]and regional security concerns were often construed by ‘old Europe’ as unenlightened.[12]

If the 2014 annexation of Crimea was a turning point for Polish defence policy, Russia’s full-scale war in Ukraine marked an epochal shift. Thus, during the last decade, Poland began forming volunteer Territorial Defence Forces (WOT), increased defence spending to 3 per cent of GDP, and engaged in army modernisation and personnel enlargement while also revising key strategic documents like the National Security Strategy and the Homeland Defence Act.[13] These changes have also signalled a paradigm shift towards comprehensive defence – a model that engages state actors, critical enterprises, civil society and individual citizens alongside the army.[14] In this context, resilience mainstreaming has been integrated into key state institutions, e.g. crisis management trainings for railway workers and foresters conducted by WOT. At the same time, security knowledge and skills are increasingly disseminated in society, e.g. through short volunteer trainings for civilians offered by the Ministry of Defence (Train with the military and Train like a soldier) as well as a Get Ready survival manual for citizens prepared by the Government Centre for Security.

Paramilitary civil society

Rather than proceeding from top to bottom, this shift was preceded by decades of efforts to remake defence ‘from below’ through grassroots organising, discourse shaping, and campaigning. At the forefront of these changes were paramilitary NGOs – volunteer associations dedicated to the strengthening of national defence. The first two associations – ZS ‘Strzelec’ formed in 1989 and ZS ‘Strzelec’ OSW established in 1990 – were inspired by the pre-World War I traditions of the Polish Riflemen’s Association. Over the years, the sector has grown and diversified: it numbered around 200 local units and 30,000 active members in 2015.[15]

While non-governmental in character, the sector maintains a statist and law-abiding ethos, and sees itself as the societal arm of state defence.[16] Its paramilitary organisations hark back to older Polish traditions of guerilla warfare and total defence involving a broad spectrum of citizens. While training is their main line of work, paramilitary NGOs also contribute to broader societal resilience by providing local communities with assistance, engaging in addiction prevention, and promoting the ideal of a ‘resilient, caring and capable’[17] citizenry. Some organisations have also sought to influence public opinion and policy by mobilising awareness about the need to rebuild territorial defence formations.

With the current shift in defence policy, these actors and their innovations have been increasingly brought under state control and given support in the form of Ministry of Defence grants, forming part of the MOD Consultation Board on pro-defence issues, for instance. With new forms of military service being offered by the state, some paramilitary NGOs ceased to exist, and many members joined WOT. Since the Russian invasion, the sector has also been actively engaged in providing aid to Ukraine, with some individual members and organisations even receiving Ukrainian state awards.

Vernacular change

While not large-scale in terms of its size and reach, paramilitary civil society provided a blueprint for state-led comprehensive defence reforms. Initially, the model promoted by the sector did not enjoy much popularity, given that it was contrary both to the powerful post-Cold War ‘end-of-history’ Zeitgeist and NATO’s expeditionary concept. By exposing the blind spots of the ‘postmodern’ European security turn, the war in Ukraine opened up a space for the mainstreaming of the sector’s whole-of-society approach. As one paramilitary commander told me, ‘first they laugh at you, then they try not to notice you, and eventually they say they wanted the same thing as you from the beginning.[18] Arguably, what aided this process has been the support for this broader ‘culture of defence’ in the wider society. As shown in different public opinion surveys, Poles have so far exhibited a strong societal and cross-party consensus on geopolitics and defence policy. A striking 95 per cent of Poles want to stay in NATO and 88 per cent see Russia as a threat;[19] most support higher military spending and army enlargement;[20] and 66 per cent are willing to defend the state.[21] Following the 2023 change of government, some procurements and plans will be adjusted, yet no major shift in defence policy is expected given that the newly elected parties voted in favour of the Homeland Defence Act in 2022.

Finnish security perceptions and the securitisation of borders with Russia

Joni Virkkunen is a Research Manager at the Karelian Institute and Director of the VERA Centre for Russian and Border Studies at the University of Eastern Finland (UEF). Since receiving his PhD in 2002, his tasks have been related to research and research coordination in the fields of Russian and border studies and doctoral training at the UEF.

> Homepage

Russia’s war against Ukraine has had huge direct and indirect impacts on Finland’s security. Despite the country’s former tendency to emphasise pragmatism and good relations with Russia, Russia’s attack against Ukraine, another small sovereign state in its neighbourhood, brought back memories of World War II and the implicit Soviet pressure on Finland’s foreign policy. Finland lost 96,000 citizens and up to 12 per cent of its territory to the Soviet Union in that war and, despite keeping its de facto independence, much of Finland’s relationship with its Eastern neighbour was characterised by a superficial neutrality and mutually friendly relations. Those relations were formally regulated by the Finnish-Soviet Agreement of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance (YYA Treaty), signed in Moscow on 6 April 1948 and informally in force until it expired in 1992.

The historical memory of World War II has thus strongly impacted Finns’ perceptions of Russia and Russian nationals, as well as Finland’s sense of security. Beyond the war and military operations in Ukraine, it has become clear to Finland that Russia is also exercising hybrid warfare in its confrontation with the West. Besides economic sanctions and the severing of diplomatic ties, Russia’s policies against countries that it defines as ‘unfriendly’ include diverse strategic non-military coercion measures such as cyberattacks, disinformation and other hybrid operations, including the use of migration, energy, or the environment as ‘weapons’ and tools in its international politics. For instance, in 2015 and 2016 Russia opened its northernmost border crossings with Norway and Finland for third-country asylum seekers hoping to get to the EU. When a similar incident occurred in November 2023 and over 900 asylum seekers entered Finland from Russia, the Finnish government decided to close its entire eastern border and stop all traffic from Russia. The arrival of those asylum seekers was, the government justified, ‘aided by foreign authorities or other actors’ who posed ‘a serious threat to national security and public order in Finland.’[22]

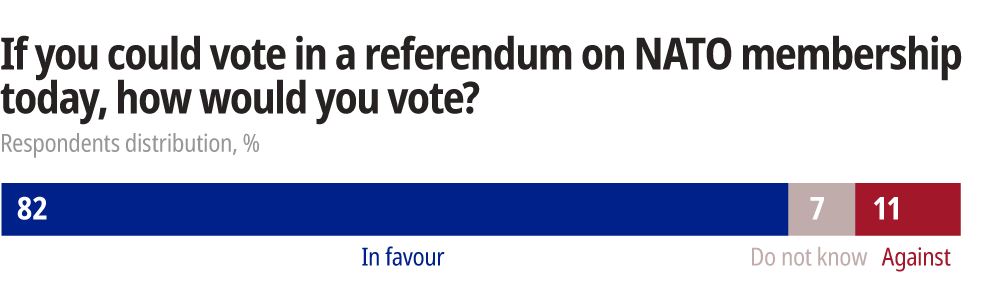

Finland’s policy towards Russia turned from pragmatic to explicitly defensive: only two months after Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Finland applied for membership in NATO and became a full member of the alliance on 4 April 2023. Additionally, on 18 December 2023, Finland’s Minister of Defence Antti Häkkänen and United States Secretary of State Antony Blinken signed the bilateral Defence Cooperation Agreement (DCA), clarifying the rules for cooperation and allowing the parties to deepen it in all security situations. This rapid change in Finland’s defence policy reflected the swift increase in public support for joining Western military alliances and meeting Finland’s clear need to strengthen its military defences in an entirely new security environment. In a matter of months, public support for NATO membership increased from about 25 per cent of the population in 2021 to 60 per cent in March 2022 and 78 per cent in October 2022.[23] This support for NATO membership has remained at a record high and, according to a NATO poll conducted in June and November 2023, up to 82 per cent of respondents would vote in favour of joining the alliance if a referendum on that question was conducted now, and up to 65 per cent were in favour of the DCA with the USA.[24] At the same time, an increasing number of men and women expressed their interest in personally investing in Finland’s security by joining various voluntary national defence associations such as local branches of the National Defence Training Association.[25]

Figure 1. Support for Finland’s NATO membership, June 2023

This new tendency to fortify and militarise Finland’s eastern border with Russia has been the subject of much public debate. According to the former Minister of the Interior, Krista Mikkonen, the barrier fence will help to slow and guide irregular border crosses in areas of risk while, at the same time, taking into account both the limited human resources and available tactics and technology of the Finnish Border Guard.[28] Despite its projected benefits for border management, the discussion of the fence is not based on empirical facts but on assumptions, which may well create a false sense of security. Finland’s NATO membership and the fortification of the border are supposed to increase Finland’s defence and border management capacities. Despite strong public and political demand for a border barrier fence, it is openly acknowledged that the fence is merely symbolic. It responds neither to the critiques levelled by border scholars with extensive comparative evidence from other bordering contexts nor to vernacular conceptions of security in borderlands.[29] As the Arctic route migration during the 2015-2016 ‘refugee crisis’ and the rapid increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving from Russia in November 2023 demonstrate, the fence that is estimated to cost taxpayers EUR 380 million does not necessarily prevent Russia from opening its border crossing points for asylum seekers to Finland. And if the actual purpose of the fence is to respond to Russia’s military threat, it will not be sufficient to prevent Russia from attacking Finland militarily if it so wishes.

All cooperation with Russian institutions and individuals working for them has come to an end. Mutual sanction regimes, border closures and a dramatic severing of cross-border ties, combined with strong stereotyping, will have long-term effects on both the border and the border area that go far beyond the militarisation of the state. To limit a possible new ‘wave’ of irregular border crossings, on 9 November 2023 the Government of Finland banned border crossings by bike at the southeastern border crossing points; on 18 November it closed border crossing points along the southeastern section, and four days later, along all sections of the Finnish-Russian border. Despite some criticism by border scholars, migration lawyers and activists,[30] and by Finland’s Deputy Chancellor of Justice,[31] this border closure was extended initially until mid-February 2024. However, on 4 April the Government decided that all border crossing points along Finland’s eastern border will remain closed until further notice.[32] Thus apart from military defences, borders, cross-border migration and Russia’s hybrid operations are central aspects of Finland’s national security.

Russia’s immediate neighbourhood: Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus

Weaponisation and its reverse: Implications for Ukraine’s security

Yuliia Kurnyshova is a Postdoctoral Researcher at the Department of Political Science, University of Copenhagen. Her current research project explores the political and security implications of the Russia’s war against Ukraine. She graduated from Kyiv National Taras Shevchenko University, where she obtained Masters Diploma in History and Journalism.

In Ukraine, the caesura of February 2022 has had another significance compared to the other country cases in this report, since it has been and still is at the centre of Russia’s war of aggression. On both sides, this war is driven by the logic of a weaponisation of non-military resources, which creates chains of insecurities in such interconnected domains as energy, the environment, food, and transportation. However, the so-called ‘weaponisation of everything’ has its limitations, and is countered by a logic of de-weaponisation meant to detach certain spheres from the purview of security. Arguably, de-weaponisation takes different forms, most of which are beneficial to Russia and detrimental to Ukraine’s overall security strategy.

Weaponisation is based on the weaponiser’s intention to transform material (for example, extractive industries) or non-material (for instance, history) resources into tools for achieving security goals against an adversary. The targets of weaponisation may either recognise that certain resources are being turned into weapons and used against them, or – implicitly or explicitly – deny that this is the case.

The logic of weaponisation pervades the broad spectrum of insecurities created by Russia’s war of aggression. Before the invasion, the prevailing approaches to conflict were grounded in the distinction between hard, soft and smart power and the separation of resources into different ‘baskets’ – cultural, economic, financial, industrial, political and military. Thus Western economic and energy relations with Moscow continued to develop despite Russia’s wars in Georgia and Syria and the annexation of Crimea.

Yet Russia’s full-scale intervention in Ukraine in 2022 weaponised a broad range of material assets (supply chains, logistics, economic transactions, technologies), alongside such ideational spheres as memory politics or information management. Traditionally non-military spheres have become part and parcel of military warfare, as evidenced by the emergence of new concepts like ‘mineral security’. The logic of weaponisation is conducive to the simultaneous unfolding of interconnected crises. Russia’s war against Ukraine provoked a food supply crisis that severely affected global markets; triggered a mass exodus of Ukrainian war refugees to Europe; and set the stage for Europe’s painful decoupling from Russian energy resources. Cyber, maritime and environmental insecurities can be added to this list. The overall impact of these overlapping insecurities on international relations is more than the sum of each individual insecurity.

In most cases, Western governments’ reactions to Russia’s weaponisation brought benefits to Ukraine. Thus, when Russia weaponised the gas supply to the EU by cutting its pipeline deliveries by more than three-quarters, the EU introduced a sanctions regime against Russia and renewed its commitment to qualitatively decreasing the importance of oil, gas, and coal in the economy, which opened up opportunities for Ukraine as an exporter of electricity. Despite the fact that up to 50 per cent of its energy infrastructure has been destroyed, Ukraine has managed to continue exporting electricity to Poland and Slovakia, two partners that are providing it with weapons. In addition, due to the war Ukraine has integrated faster than initially planned into the European Union’s joint energy system (ENTSO-E).

Yet there are other developments that are not consistent with the weaponisation paradigm. Some EU and NATO member states prefer to act in their own economic interests rather than within the framework of weaponisation and counter-weaponisation. Just five months after EU members states agreed on tariff-free exports of Ukrainian grain to Europe, the governments of Poland, Slovakia and Hungary turned their backs on this deal. Here, the interests of local agricultural lobbies took precedence over a common security agenda, creating tensions between Kyiv and its Central European neighbours and undermining efforts to formulate a uniform security response to Russia’s blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports.

Different mechanisms aimed at avoiding sanctions and continuing trade with Russia are another example of de-weaponisation in the economic sphere. Some European countries continue to trade with Russia through third parties. For example, after February 2022 exports from Germany to Kyrgyzstan rose by some 949 per cent, sparking concerns that the re-exportation of goods from neighbouring states is helping Russia circumvent sanctions.

Russia’s weaponisation of immaterial resources like information is also not always recognised and dealt with in the West. A pertinent example is the 2023 Valdai Discussion Club (a yearly Russian forum for political discussions) patronised by the Kremlin and attended by 140 international experts from 42 countries, including some EU and NATO member states. Their engagement with the Valdai Discussion Club corresponds to the logic of public diplomacy that was mainstream in peacetime, but nowadays seems to be detached from the reality of the Putin regime’s strategic use of narratives as a war instrument.

With this in mind, Ukraine might benefit from those policies of its Euro-Atlantic allies that are built on the recognition of Russia’s weaponisation of multiple resources and aim at the counter-weaponisation of spheres where Moscow is particularly vulnerable such as finance, investment, and technologies. Far more detrimental to Ukraine are the policies of states and non-state actors that shrink from resisting Russia’s weaponisation and pursue their own particular goals and interests.

Russia’s weaponisation of non-military domains has so far been effectively counteracted by Ukraine’s strategic adaptability and resilience and Western support. The state of being under attack has catalysed strong national cohesion in Ukraine, but the long-term societal impact hinges on successfully striking a balance between defence and normalisation. Adaptability has its limits, and it is imperative that the trend to counter-weaponisation prevails to sustain societal resolve and cohesion. The promise of European Union and NATO integration remains a driver of Ukraine’s future development. Moreover, the ongoing conflict has crystallised a crucial understanding for the West: maintaining a rules-based international system is predicated on the capacity to enforce those rules effectively. Reinforcing the West’s stability through partnership with and defence of Ukraine is a more viable route than the previous reliance on relations with Russia.

Moldova’s National Security Strategy and societal cohesion

Inna Șupac works as an expert in good governance and public policy at the Institute for Strategic Initiatives (IPIS) in the Republic of Moldova. Prior to this, Inna was involved in politics as a member of parliament for ten years. She contributed to the In:Security Report while a research fellow at the Academy for International Affairs NRW in Bonn. > Homepage

Inna Șupac works as an expert in good governance and public policy at the Institute for Strategic Initiatives (IPIS) in the Republic of Moldova. Prior to this, Inna was involved in politics as a member of parliament for ten years. She contributed to the In:Security Report while a research fellow at the Academy for International Affairs NRW in Bonn. > Homepage

The Russian aggression against Ukraine has had severe economic and social consequences for Moldova, and the situation has been exacerbated by the energy crisis and inflation, which in August 2022 was the highest in the region. This was the context in which President Maia Sandu presented the draft of a new National Security Strategy in October 2023, which was adopted by Parliament two months later. [33]

Comparing the new National Security Strategy to its predecessor, [34] some old threats remain, among them corruption, poverty, energy dependence, the Transnistrian conflict, demographic decline, and environmental pollution. In addition to old risks and vulnerabilities, such as global or regional economic crises and terrorism, the Strategy mentions a number of new ones: an insufficiently reformed justice system; an army lacking in equipment; the reduced administrative capacity of public institutions; misinformation; insufficient integration into the European energy market; limited transport infrastructure and connectivity with immediate neighbours; and cyberattacks. Opinion poll data from June 2023[35] and August 2023[36] show that price development, a war next door, children’s future, poverty, and corruption are the problems that Moldovan citizens are most concerned about. Thus, the Strategy appears to largely reflect the people’s main concerns and insecurities.

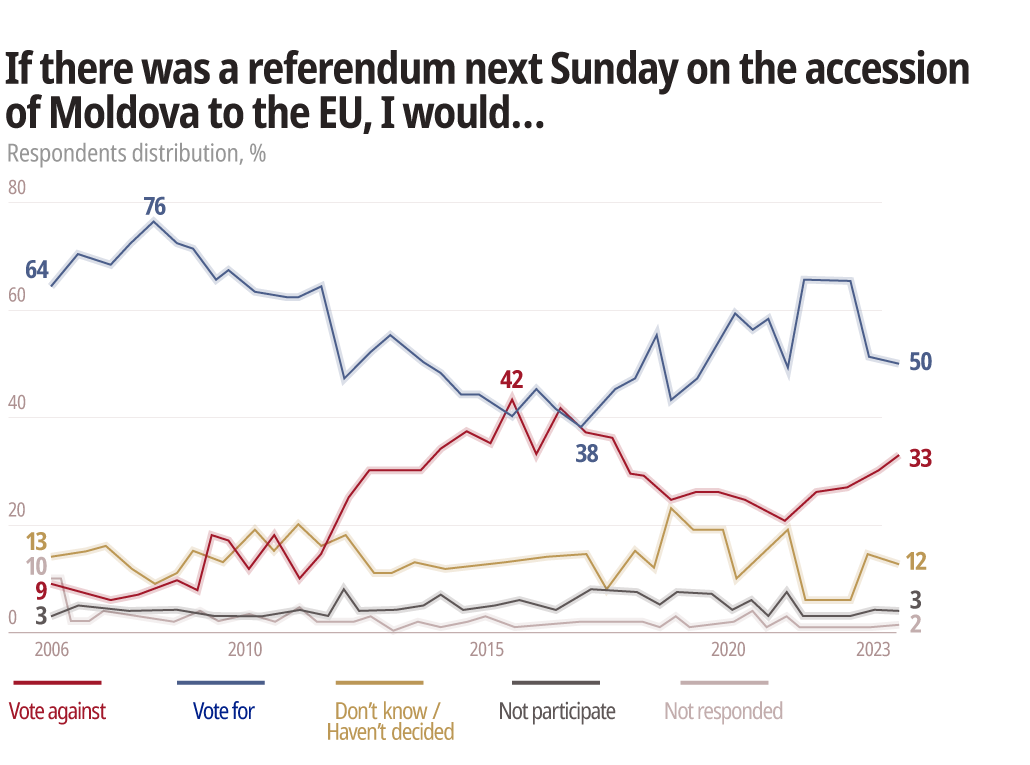

In the preamble to the Strategy, President Sandu outlines her vision for the Republic of Moldova as a member of the EU by 2030. Yet, this is not a vision shared by the majority of Moldovans. The latest reliable data show that support for EU membership among Moldovan citizens hovers at around 50 per cent (Figure 2). Indeed, the sharp division of Moldovan society could become the main obstacle to making the country’s process of European integration irreversible. From this perspective, the main problem is that the government’s Strategy does not address the most significant risks to Moldovan national security, namely the lack of social cohesion and a national consensus on the accession of the Republic of Moldova to the European Union.

Figure 2. Popular support for EU membership

Source: Institute for Public Policy (Republic of Moldova), 2023, Link

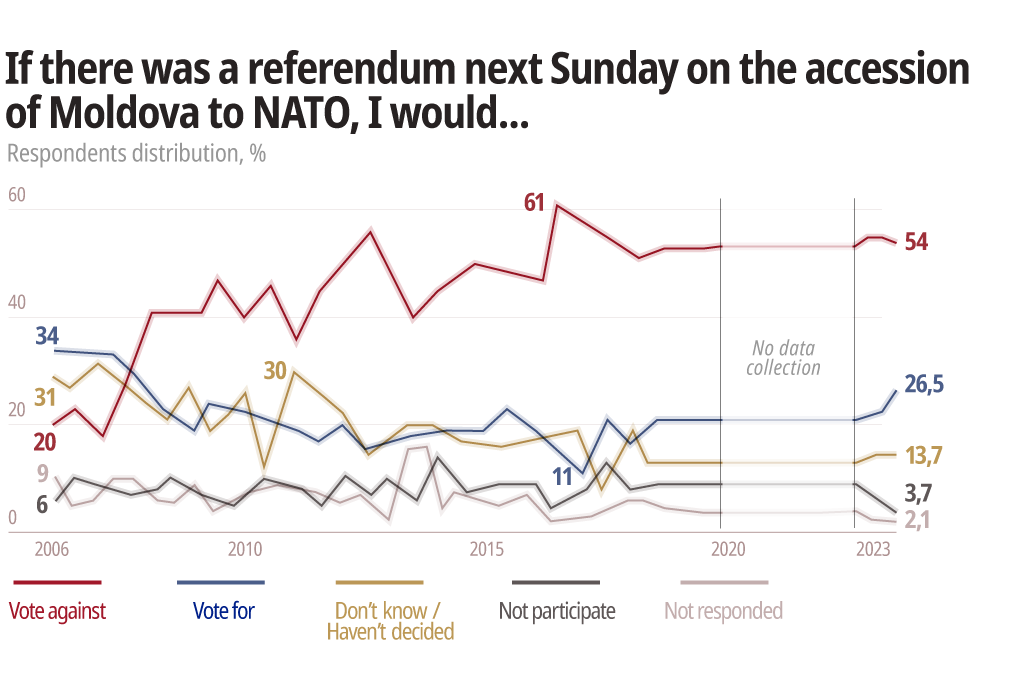

In the new Strategy, there is furthermore no mention of the neutrality enshrined in the Moldovan constitution. This is at odds with popular opinion in the country, where only up to 30 per cent of citizens are ready to support Moldova’s accession to NATO (Figure 3). Yet the authorities insist on allocating additional financial resources to modernise the army and the country’s defence capabilities. For the first time since the Republic of Moldova gained independence, the Strategy states that the Russian Federation represents the most dangerous threat to the country’s security. But at the same time there is a clear lack of direct dialogue with Moldovan society, especially with the ‘other’ part of Moldova which is more sceptical about the country’s path to the EU.

Figure 3. Popular support for NATO accession

Source: Institute for Public Policy (Republic of Moldova), 2023, Link

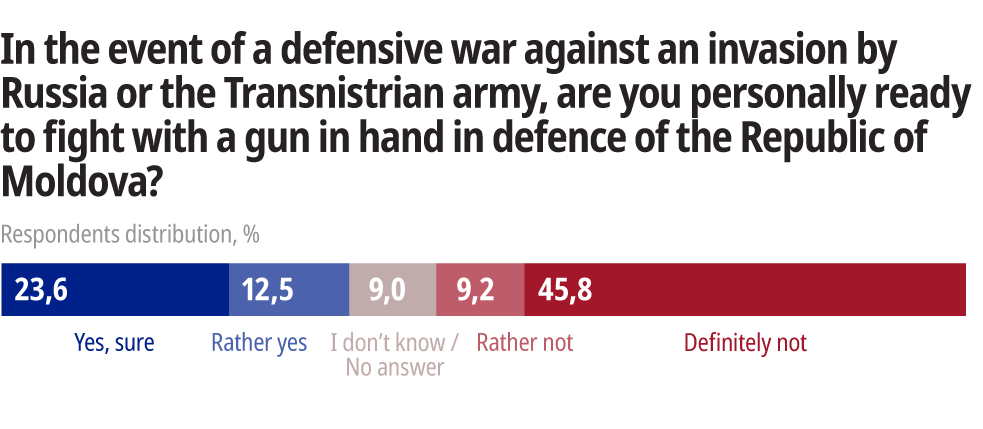

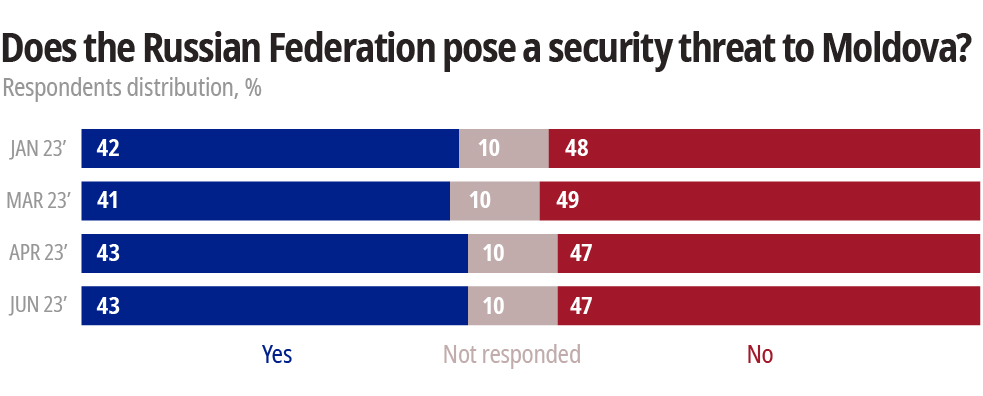

Since February 2022, new fears have been added to existing ones. An official statement that accession to the EU is not the same thing as unification with Romania would probably allay deep-seated fears, especially among residents of Gagauzia and Transnistria, but so far none has been issued. Firm assurances of respect for the country’s neutral status would also allay both the old fear of accession to NATO and the new fear of provoking Russia to attack Moldova, in which case 55 per cent of citizens say they are not willing to take up arms in defence of Moldova (Figure 4).[37] Citizens are divided in their views of Russia: 42 per cent agree that Russia should be treated as a security threat, and 47 per cent disagree with this (Figure 5). This disunity cannot be attributed solely to Russian propaganda. Rather, it shows how most of the population are fed up with the authorities’ attempts to explain their lack of progress in overcoming internal problems with reference to Russia’s war against Ukraine and its hybrid war against Moldova. The more the pro-European government refuses to promote a broad dialogue, the more scope there will be for discrediting the European pathway and the more detrimental that will be to the social peace.

Figure 4. Societal readiness to defend the nation against a Russian attack

Source: Watchdog.md, 2023, Link

Figure 5. Societal perceptions of Russia as security threat

Source: Watchdog.md, 2023, Link

The data suggest that the lack of social cohesion and national consensus on the accession of the Republic of Moldova to the European Union are the most significant risks to Moldovan national security. The decision to join the EU and the projected date of accession are not irreversible. Allocating resources for the modernisation of the Moldovan army and the country’s defence capabilities is a cosmetic move. Ultimately, the resistance of the Ukrainian people will decide whether, even in the unlikely event of an attack by Russia on Moldova, the country’s integration with the EU will be feasible. However, there are other more likely threats that could still jeopardise the country’s EU integration path. The progress so far made could be reversed if support for this project is lacking in the population, and this scenario could already happen in the aftermath of the next parliamentary elections in 2025. In that event, a revival of the oligarchic system cannot be ruled out. Hence, the risk of democratic backsliding is yet another fundamental insecurity that Moldovan society is faced with.

The monopolisation of the idea of EU integration by one political party and/or political leader can be an insurmountable obstacle to achieving nationwide consensus. Efforts to promote an inclusive dialogue with different parts of Moldovan society, including political parties, with a view to achieving a national compromise on EU accession may foster social cohesion based on a common desire for internal modernisation, improved living standards, and peaceful reintegration of the country.

Divided Belarusian society and the potential consequences of emerging insecurities

Andrei Kazakevich is the director of the Institute for Political Studies ‘Political Sphere’ (Minsk, Belarus) and a research fellow at the Lithuanian Institute of History (Vilnius, Lithuania). He is an analyst and political scientist, specialising in Belarusian and Eastern European politics and foreign policy, the judicial system, and post-war political history. > Homepage

Belarus is one of those countries where rather than consolidating society, Russia’s war against Ukraine has divided it. Although sympathies towards Russia remain, the overwhelming majority of the population is against a direct participation by Belarus in the war.

In assessing the potential consequences of emerging insecurities in Eastern Europe, it is important to take into account the peculiarities of the political system in Belarus. Belarus is a consolidated autocracy, where the policies of the leadership depend very little on public opinion. Thus, it is the actions of the authorities, and not public sentiment, that determine the emergence and persistence of security risks. The gap between the authorities and the public mood has widened significantly as a result of the political crisis of 2020 and further repressions by the state. If before 2020 Lukashenko was a populist for whom the sympathy of the majority was important, now the main political strategy of the authorities is to implement their decisions regardless of public sentiment.

Thus, conflicting attitudes towards the war and widespread anti-war sentiment have no significant influence on the authorities’ policy of supporting Russia’s expansionist policies, and thus creating new security threats in the region. On most issues, public opinion is ignored. Probably the most tangible consequence of the authorities ignoring public opinion is out-migration, which was never higher in the entire history of independent Belarus, and creates problems for the labour market and the economy. It is expected that this migration will considerably worsen the demographic situation and the outlook for growth and long-term economic development.

In the following, the main threats to security posed by the current situation will be outlined.

Service provider for the Russian military

The Belarusian authorities allowed Russia to station troops on Belarusian territory for an attack on Ukraine. There is no reason why this cannot be repeated in the future in relation to any neighbouring country. The Belarusian authorities have made no statements to the contrary. Now, the possibility of a new war between Russia and European countries is being discussed at different levels. Although at present such a threat is rather hypothetical in nature, since Russia does not have the resources for a new military campaign, such a scenario may arise after the conflict in Ukraine has been frozen.

Perhaps the most visible threat to regional security stems from the ability of the Belarusian defence industry to help rebuild Russia’s military capabilities. Belarus supplies weapons to Russia and provides repair and maintenance services for equipment. These capacities will remain important as the war continues.

Currently, Russian troops are still stationed in Belarus and their number can be increased at any time. We saw this when units of the ‘Wagner’ private military company were temporarily deployed on the territory of Belarus in the summer of 2023. The main limiting factor here is again Russia’s lack of capabilities to deploy new forces as the war in Ukraine consumes all its resources.

The Belarusian authorities have agreed to the deployment of tactical Russian nuclear weapons on their territory, which could pose a potential danger to their neighbours. At present, it is not clear whether such weapons are actually located on the territory of Belarus. The idea is not popular among Belarusians, but the Belarusian authorities claim that such weapons will increase their own security.

Militarisation of Belarus

The Belarusian authorities are taking measures to strengthen their defence capabilities, so the risk of a militarisation of Belarus remains. The potential for this, however, is greatly limited due to the country’s lack of financial resources and the weakening of Russia’s ability to supply it with military equipment and arms. The main focus is on developing territorial defence rather than increasing the size and potential of the armed forces, whose combat effectiveness is currently extremely doubtful. Thus, the main investments do not go to the army, but to the security forces and the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Regional security authorities completely rely on Russian military strength, and that is why their main priority has been to increase capacities for eliminating internal threats and possible unrest. In this context, the right of members of the state service to carry arms has been expanded, military training for university students has been introduced, paramilitary groups have been organised, etc.

Instrumentalisation of migration

Starting in 2021, the main leverage that the Belarusian authorities tried to use against neighbouring countries was cross-border migration from third countries, which peaked at the end of 2021, but continued until the autumn of 2023. It is likely that they will resort to these tactics again, even though the stimulation of cross-border migration failed to have the desired influence on neighbouring countries. In addition, neighbouring countries have a significant deterrent (border closures), which in the long run could be detrimental to the interests of the Belarusian authorities, who want Belarus to remain a transit country for migration from from Asia, especially China, to Europe.

Risks for the population of Belarus

The whole situation entails significant risks for the population of Belarus, especially for people with pro-European and anti-war views. On the one hand, political repression in Belarus is likely to continue and intensify. On the other hand, the citizens of Belarus are becoming increasingly isolated from European countries, and thus more affected by Russian disinformation.

If the situation does not change, then a continued significant outflow of people of working age from Belarus is likely in the medium to long term, as well as economic stagnation and technological backwardness. The gap in living standards and opportunities between Belarusians and their European neighbours will widen, increasing the regional marginalisation of Belarus and the growth of internal tensions.

An increase in societal inequalities and divisions can also be expected, as the few remaining resources will be distributed primarily among supporters of the current government and the state apparatus. The authorities have repeatedly voiced the idea that the distribution not only of career opportunities, but also social benefits, should be linked to loyalty to the current system. In the long term, this will only deepen internal societal conflict in Belarus.

South Caucasus: Georgia and Armenia

The Influx of Russian migrants to Georgia – a factor of insecurity?

Kornely Kakachia is Jean Monnet Chair and Professor of Political Science at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Georgia. He is also the director of the Tbilisi-based think tank Georgian Institute of Politics. His current research focuses on Georgian domestic and foreign policy, security issues of the wider Black Sea area and comparative party politics. > Homepage

Kornely Kakachia is Jean Monnet Chair and Professor of Political Science at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Georgia. He is also the director of the Tbilisi-based think tank Georgian Institute of Politics. His current research focuses on Georgian domestic and foreign policy, security issues of the wider Black Sea area and comparative party politics. > Homepage

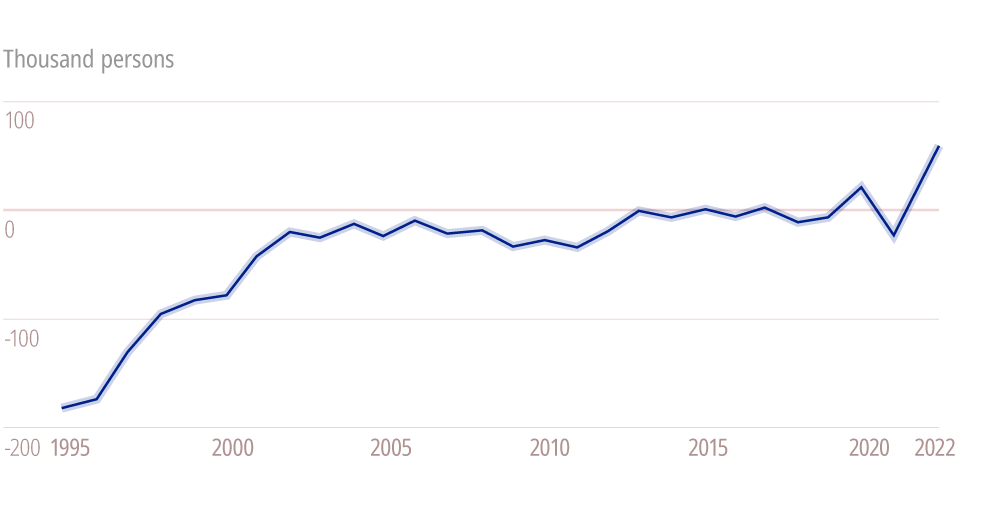

In recent years, Russia’s influence over Georgia has manifested itself in both conventional and hybrid threats, with the latter intensifying, particularly in the form of migration. The migration of Russian citizens to Georgia peaked in 2022 in connection with the Russian war in Ukraine.[38] This peak marks a significant shift in the geopolitical dynamics of the region and underscores the evolving nature of Russia’s hybrid power, where migration is increasingly leveraged as a strategic tool.[39]

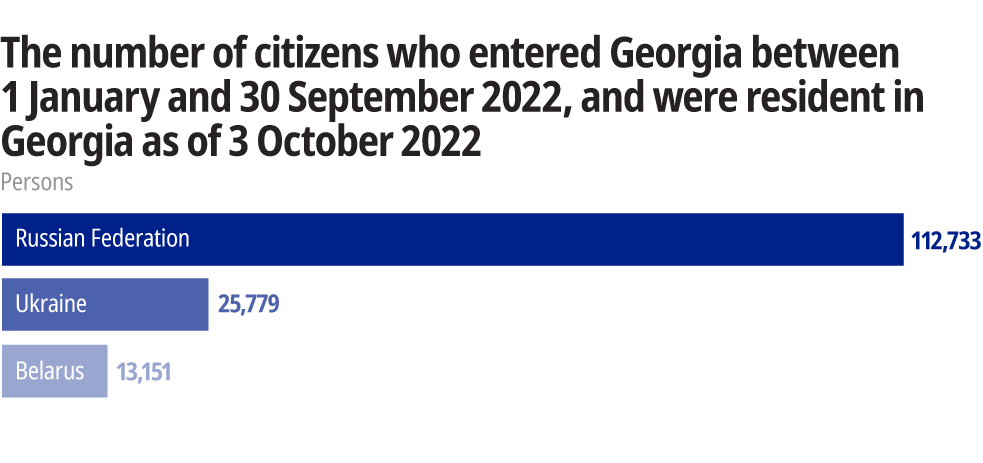

Russian immigration and its implications

Since 2022, approximately 100,000 Russian migrants have entered Georgia, although not all have received immigrant status.[40] Official statistics from 2022 show that 62,304 persons from the Russian Federation were registered as immigrants, a figure six times higher than the previous year.[41] This influx has dramatically altered Georgia’s security, socio-economic, and political landscape. The diverse consequences of this migration are influenced by the different socio-economic backgrounds of those crossing the border.[42] Attitudes towards Russian migration and its economic effects vary among state officials, expert communities, and the general public. Some view the presence of Russian migrants as an economic benefit, while others perceive it as a security and political risk.

Georgia faced three waves of Russian migration between 2022 and 2023. The start of the war in Ukraine was the general push factor driving Russian citizens out of Russia. In the first wave, the primary motivation for migration was the economic fear of losing wealth due to Western sanctions and the expulsion of Russia from Swift. This migration phase was underpinned by a perception that life in Russia would not be the same for an indefinite period, leading to fears related to wealth, physical safety, employment and political stability. The pull factors for Russian migration to Georgia are manifold. Georgia’s geographical proximity to Russia and the availability of various transport links, including land, sea, and air travel, as well as cultural and religious factors make it an accessible destination.

Figure 6. Net Migration to Georgia

Source: Geostat, Link

The second wave since September 2022 consisted mainly of males who wanted to avoid conscription. Georgia became a ‘safe haven’ for Russian citizens because they have the right to stay there visa-free for effectively one year.[43] While the government has taken a laissez-faire attitude to it, the influx of Russian citizens could create imbalances in Georgia’s demographic structure, considering that the Georgian population is a mere 3.5 million. The third wave can be dated to the opening of direct flights between Moscow and Tbilisi in May 2023. Georgian public opinion was divided on this issue, and the government justified the move by claiming it would help the Georgian diaspora in Russia.[44] Georgian economic and security experts are concerned, however, that economic dependency on Russia will not be beneficial to Georgia’s economy or security in the long run.

Figure 7. Number of Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian Citizens in Georgia

Source: Ministry of Internal Affairs of Georgia, 2022, Link

Russian migration is increasing insecurity in Georgia in various ways. In the short term, the presence of over 22,400 Russian companies in Georgia may result in the social exclusion of Georgian citizens on the labour market. [45] The inflow of Russian capital into – as well as Russian ownership of – infrastructure projects presents further economic risks. Concerns have also been raised regarding the demographic and political impacts of Russian migration due to Georgia’s size and the significant number of Russian migrants residing there. If Russians decide to obtain Georgian citizenship, they will gain voting rights, potentially increasing the number of pro-Russian voters in the electorate.

Another factor of insecurity is the risk of sabotage by Russian operatives crossing the Georgian border disguised as Russian migrants. This threat is real: several individuals have already confessed to being dispatched to Georgia as intelligence officers of the Russian Federal Security Service.[46] Yet another security challenge relates to the high concentration of Russians in Georgia, which could make the country especially susceptible to Russian propaganda. In this regard, the rise in the acquisition of Georgian real estate by Russians, as well as their growing involvement in the education sphere, seen in their founding of Russian schools and placement of Georgian students in Russian universities, are a particular concern.[47]

Migration: Opportunities and risks

While migration and greater mobility facilitated and contributed to Georgia’s economic development, it also led to greater competition and rising prices, increasing the risk of conflicts between migrants and locals due to cultural mismatches and historical memories. Given Russia’s imperial legacy and historic annexation of Georgia, as well as the ongoing occupation of 20 per cent of Georgian sovereign territory by the Russian Federation, a negative perception of Russia persists in large parts of Georgian society.

Socio-economic and security risks

The influx of Russian citizens into Georgia entails socio-economic and security risks, including increased dependency on Moscow. [48] Given the diversity of opinions on Russian migration in Georgia, it will be difficult to manage these risks while reconciling economic benefits with societal cohesion and security concerns. The Georgian government is driven by a desire to secure electoral support; it argues that the surge in Russian migration has boosted economic collaboration with Russia, thereby fostering economic growth and stability. The general population is more ambivalent. On the one hand, people are apprehensive about the implications of Russian migration on Georgia’s economic ties with Russia; on the other hand, there is resistance to migration from Russia due to the adverse effects it has on daily life, including increased prices, intensified competition in the labour market, and a heightened sense of insecurity.

Democratic governance amid complex dynamics

These developments present significant challenges to Georgia’s democratic governance. Balancing the economic benefits of Russian migration with the challenges of societal integration, cultural conflicts, and security concerns requires adept governance and policymaking. [49] In this context, upholding democratic principles will be crucial for the stability and integrity of the Georgian state.

Armenia’s Post-War Security Conundrum: Contemplations after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

Asbed Kotchikian is an Associated Professor and Program Chair of International Relations and Diplomacy program at the American University of Armenia (AUA). He received his PhD from Boston University with a dissertation on the foreign and security policy of small states. > Homepage

Asbed Kotchikian is an Associated Professor and Program Chair of International Relations and Diplomacy program at the American University of Armenia (AUA). He received his PhD from Boston University with a dissertation on the foreign and security policy of small states. > Homepage

For Armenia and Azerbaijan, the ongoing war in Ukraine has been overshadowed by developments closer to home: the renewed war between Armenia and Azerbaijan over the Armenian-populated enclave of Nagorno-Karabakh in September 2020; the subsequent deployment of Russian peace-keeping forces; and the forced deportation of the enclave’s Armenian population in autumn 2023.

Until the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, Armenia still viewed Russia as a reliable partner and guarantor of its security. While it cannot be stated with absolute certainty, Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine registered relative apathy in Armenian society, which was still recovering from the crushing defeat it had suffered the year before. Armenia’s straying from Moscow’s orbit may be attributed more to the regime change in the country in 2018 and overtures made by the new government to the West rather than to developments in Ukraine.

Known as the ‘Velvet Revolution’, the events of 2018 aimed to dismantle the longstanding ‘competitive authoritarian’ regime and address internal socio-political issues in the country.[50] Questions subsequently arose as to whether Armenia’s new regime would take a different course in the country’s policies towards Russia and edge more towards the West, as was the case with other ‘colour revolutions’ in Georgia and Ukraine. Despite assurances by the new Armenian government that Armenia-Russia relations would remain unchanged, public rhetoric and efforts to promote more Western-Armenian collaboration raised expectations that Armenia would not remain Moscow’s undisputed ally.[51]

It is in this context that in September 2020, Azerbaijan, aided by its ally Turkey, staged a full-scale attack to reclaim its control over Nagorno-Karabakh. Despite multiple attempts by Moscow to establish a ceasefire, the war lasted for 44 days, and Armenia eventually agreed to sign a Russian-brokered ceasefire agreement, practically relegating the security of the region’s 120,000 Armenians to Moscow.

After Russian peacekeepers were deployed along the line of contact in Nagorno-Karabakh, attitudes to Russia among Armenia’s population continued to shift. Various surveys conducted since the November 2020 ceasefire agreement showed that fewer and fewer Armenians viewed Russia as a reliable partner (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Popular opinion on Armenia’s main ally

Source: Mark Dovich, ‘Survey: Growing skepticism in Armenia about Russia, even before recent fighting’, 20 September 2022, Civilnet, Link

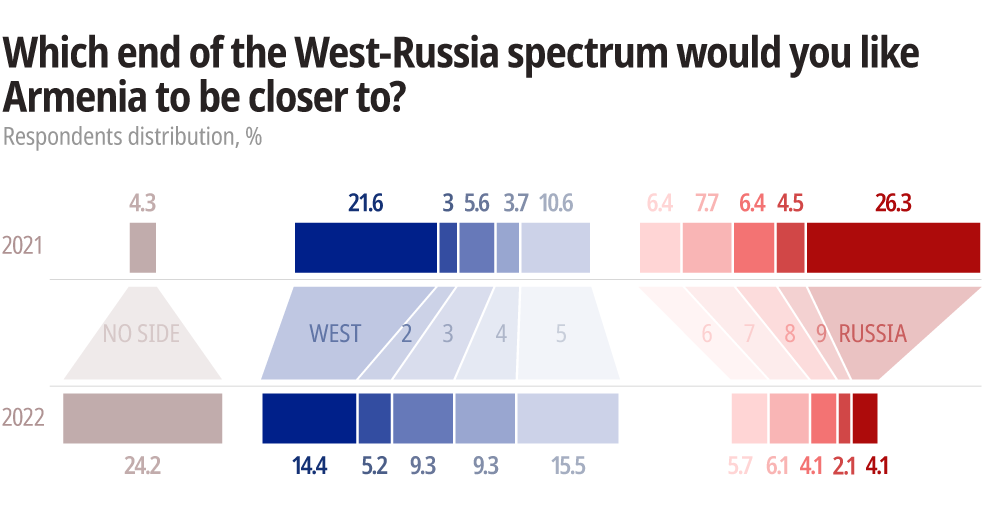

One study of attitudes to Russia among youth in Armenia in 2021 and a focus group in 2022 found an equal spread of pro-Western and pro-Russian sentiments, indicating a departure from the previous strong allegiance to Russia (Figure 9).

Figure 9. Opinions of young respondents to a 2021 representative survey in comparison with participants in the 2022 focus group discussions

Source: Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung e.V., Armenian branch, ‘Armenia’s Youth Perceptions of Russia’s War in Ukraine and its Possible Consequences: A Sociological Study’, Link

Similarly, multiple polls conducted by the International Republican Institute show how Armenia’s public opinion has shifted since 2018 from clear pro-Russia leanings to a lukewarm relationship at best.[52] In inverse proportion to that, attitudes to the EU and the West have improved dramatically.[53]

In December 2022, Azerbaijan imposed a blockade on Nagorno-Karabakh, which lasted for over nine months, and all attempts by Russia to deliver humanitarian aid were thwarted. Eventually in September 2023, Baku announced that it would lift the blockade and allow any Armenian who wanted to leave the region to do so, effectively depopulating the region of its Armenian population.

The inability of Russian peacekeepers to protect Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenian population from the almost year-long blockade by Baku and the subsequent complete depopulation of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh in autumn 2023 seems to have fuelled anti-Russian sentiment in Armenia and edged the country closer to the West. However, Armenia’s security paradigm realignment is by no means a fait accompli, as the West (in this case mostly the EU) itself is unsure about how to handle the new apparent vacuum in the minds of Armenians. Despite some cosmetic changes, including the establishment of the European Union Mission in Armenia (EUMA), Armenia’s options to replace Russia are quite limited.[54]

Alongside external security challenges arising from geopolitical shifts, Armenia also has to contend with a domestic security component related to the security of its democratic institutions and the threat of democratic backsliding. Ever since the disastrous war of 2020, ‘security vs democracy’ has been a repeated mantra in the general population and in some political groups, based on the false premise that Armenia’s democratic transition in 2018 was the main reason why the country lost the war in 2020.[55] While the danger to the country’s future democratic consolidation is not imminent, concerns to this effect are raised periodically and used by opposition groups to demand early elections, which could potentially torpedo the country’s efforts to normalise relations with Azerbaijan.

It is quite possible that neither Moscow nor Brussels are able, or willing, to act as a ‘sponsor’ of a new security architecture in the South Caucasus. However, since the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh war, an increased number of European delegations (either in the context of EU or bilaterally) have tried to support the Armenian government’s democratic reforms by focusing on institutional support for various domestic projects. The main challenge for Armenia remains balancing those reforms and leveraging them, if possible, in Yerevan’s direct negotiations with Baku for a possible peace agreement.

Concluding remarks

by Nadja Douglas

Current insecurities and fears in societies bordering the Russian Federation are not entirely the result of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022. For many of the states neighbouring Russia, 2022 was a turning point and rupture, particularly in terms of their defence postures. Mentally, the societies of Poland and the Baltic states in particular had been preparing for such a moment ever since the Russian annexation of Crimea in 2014. And for societies in North Eastern Europe, the historical memory of Russia as an occupational force dates even further back. Thus, the bottom-up impact has been more significant in traditionally militarised societies, where longstanding fears have been compounded by new threat scenarios.

This report has provided ample evidence that the events since 2022 have both polarised and united societies. The impressive solidarity and cohesion of Ukrainian society in a collective effort to counteract Russian aggression and the weaponisation of non-military domains deserves first mention here. Polish society may be divided politically, but there seems to be a broad consensus on the ‘whole-of-society’ approach to defence that even the recent change of government has not undermined. Finnish society had for a long time been divided on the question of NATO accession, but since 2022 there has been consistently high public and political approval for the decision to join the alliance. It is generally acknowledged that the militarisation and fortification of the border are mainly symbolic and not entirely in keeping with vernacular security conceptions of the border. This is especially the case in already structurally weak border regions, which do not necessarily feel the benefits of border fortification and have experienced an economic downturn due to the cessation of cross-border cooperation with Russia.

The already fragile societal cohesion in historically diverse societies, such as Moldova, Armenia, and to some degree now also Belarus, has been put under further strain since 2022. The catalysts that have raised internal social tensions have been the energy crisis, inflation, and most importantly dissent over the war in Ukraine and more generally a Western or Russia-oriented course. The consequences of this for the respective societies and economies include out-migration, further brain drain or even international isolation (as in the case of Belarus). As discussed during the workshop, over the long term a lack of societal cohesion can itself become a factor in insecurity that heightens the risk of conflict.

The report nevertheless also revealed that beyond commonalities, there are also complex differences between the country cases that do not necessarily run along national or regional borders. This concerns especially attitudes and reactions by local populations to Russian migrants (in the case of Georgia and to a lesser degree of Armenia) and cross-border trade and business with Russia. This gives rise to diverse forms of insecurity in the domains of democratic development, culture, energy and food security.

One main takeaway from the discussions during the workshop was the huge diversity of discourses and perceptions in the different countries, shaped by their histories, societies, and locations. This ultimately calls into question the perception of Eastern Europe as one homogeneous geopolitical region and suggests taking a more disaggregated approach.

The dramatic images of Ukrainian society under attack have also raised a lot of very practical questions on border security and migration as well as what citizens should do in case of an actual attack on their country. Growing insecurities have led to the emergence of grassroots actors such as paramilitary organisations in the Baltics, Finland and Poland (e.g. the Polish Territorial Defence Forces (WOT)).

In sum, this report advocates assessing societal dynamics on the sub-regional and national level in order to be able to react to emerging security needs and expectations that otherwise remain below the radar of Western policy- and decision-makers. It is time to stop treating Eastern Europe as a homogeneous geopolitical entity and instead adopt a more individualised approach to regions and entities bordering Russia. In particular, the effects of insecurity in the borderlands should be taken into account as well as the risk of increasing internal and/or transnational bordering.

Sabine von Löwis (contributor) is the head of the research cluster Conflict Dynamics and Border Regions at ZOiS. She studied Economic and Social Geography at the Technical University of Dresden (TU Dresden) and gained a doctorate at HafenCity University in Hamburg.

Anne Boden (language editor) is the english-language publications editor at ZOiS. She studied Russian and German in Dublin and Cambridge. She completed her PhD on the memory discourses around published diaries of World War II in the GDR and West Germany at Trinity College Dublin in 2009.

Iaroslav Boretskii (designer) is the infographic designer and cartographer in the KonKoop project, based at ZOiS. As a fellow scholar on the Erasmus Mundus Cartography M.Sc.,he studied Cartography, Geoinformatics and Graphic Design at Technical University Munich (TUM), Technische Universität Wien (TUW), Technische Universität Dresden (TUD), and the University of Twente (ITC Department).

Iaroslav Boretskii (designer) is the infographic designer and cartographer in the KonKoop project, based at ZOiS. As a fellow scholar on the Erasmus Mundus Cartography M.Sc.,he studied Cartography, Geoinformatics and Graphic Design at Technical University Munich (TUM), Technische Universität Wien (TUW), Technische Universität Dresden (TUD), and the University of Twente (ITC Department).

Kerstin Bischl (editor) has been the academic coordinator of the KonKoop research network at ZOiS since April 2022. She brings a cultural and global history perspective to her work. Her PhD at Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin was on gender relations and the dynamics of violence in the everyday life of Red Army soldiers from 1941 to 1945.

CONTENTS

North Eastern Europe: Poland and Finland

Paramilitary civil society – remaking defence from below in Poland

Finnish security perceptions and the securitisation of borders with Russia

Russia’s immediate neighbourhood: Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus

Weaponisation and its reverse: Implications for Ukraine’s security

Moldova’s National Security Strategy and societal cohesion

Divided Belarusian society and the potential consequences of emerging insecurities

South Caucasus: Georgia and Armenia

The Influx of Russian migrants to Georgia – a factor of insecurity?

Armenia’s Post-War Security Conundrum: Contemplations after the 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh War

[1] For more about the topic line ‘In:Security’: Link to topic line description.

[2] Barry Buzan, Ole Wæver, and Jaap de Wilde, Security: A New Framework for Analysis (Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1998).

[3] Graeme P. Herd and Joan Löfgren, ‘“Societal Security”, the Baltic States and EU Integration’. Cooperation and Conflict, 36(3), (2001).

[4] Barry Buzan, People, States and Fear: An Agenda for International Security Studies in the Post-cold War Era (Colchester: ECPR Press, 2007).

[5] Ronald F. Inglehart and Pippa Norris, ‘The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse: Understanding Human Security’, Scandinavian Political Studies 35 (1), (2012).

[6] Nick Vaughan-Willams (2021), Vernacular Border Security: Citizens’ Narratives of Europe’s ‘Migration Crisis’ (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2021).

[7] Nils Bubandt, ‘Vernacular Security: The Politics of Feeling Safe in Global, National and Local Worlds’, Security Dialogue 36(3), (2005).

[8] Anthony Giddens, Modernity and Self-Identity (Cambridge: Polity, 1991) quoted in Bubandt 2005.