Author: Gaëlle Le Pavic | 28.05.2025

Picture: ‘Controlled-crossing’ point between the villages of Phakhuliani on the Georgian-controlled side and Saberio on the Abkhazian-controlled side – August 2022 © Gaëlle Le Pavic

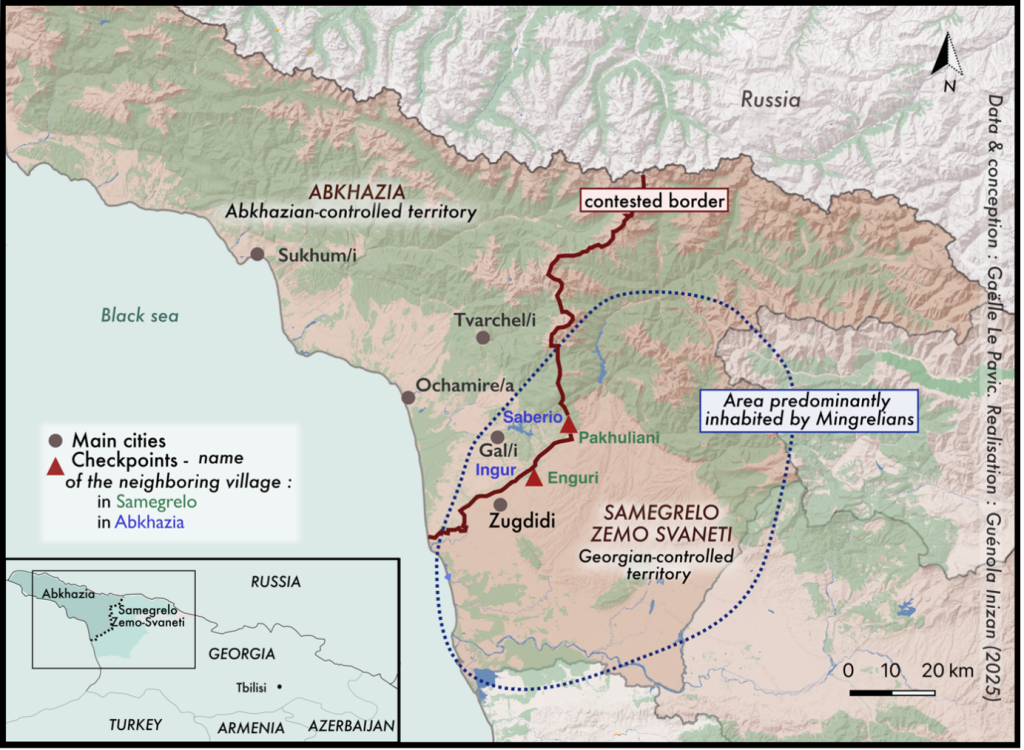

All borders are contested, but some more visibly and viscerally than others. This is especially true of the Georgian-Abkhazian divide, where even the very term border is highly disputed. In Georgia, particularly among those living far from the dividing line, it is commonly referred to as the occupation line – a phrase that reflects a dominant national narrative of Russian control over Abkhazia and South Ossetia. In contrast, those living closer to it, in the Samegrelo region, more often describe it simply as a border, speaking of their location as being on the edge of a border. On the other side, Abkhaz residents also refer to it as a border, rejecting the idea of Russian occupation and asserting Abkhazia as an independent nation-state. Meanwhile, international organisations and donor actors – entangled in the politics of non-recognition – avoid the word border altogether. Since Abkhazia has gained limited international recognition, most international actors continue to affirm Georgia’s territorial integrity. To navigate this political sensitivity, technical terms such as Administrative Boundary Line (ABL) and Tbilisi Administered Territory (TAT) have been adopted to describe the division without framing it as a border.

These multiple terminologies highlight the complex and evolving nature of this divide, which is both a material and an immaterial one between Georgian- and Abkhazian-controlled territories. More than thirty years after a ceasefire was signed, Georgians and Abkhazians continue to disagree on the territorial division. Drawing on 14 weeks of fieldwork in the Samegrelo region between October 2021 and November 2022, this blogpost offers a brief overview of the transformation of a ceasefire line into what remains until today a contested border.

What began as a ceasefire line in 1993, following a thirteen-month war between Georgia and Abkhazia, has over the past three decades been shaped by different dynamics. These include shifting material infrastructures, political discourses, and everyday practices, which have gradually transformed this divide into an assemblage of visible and invisible contested borders. Assemblage theory, as developed by Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari in A Thousand Plateaus (1980), is an interesting framework for understanding the heterogeneity, dispersion and contingency of the contested border components. The divide is not a fixed line, but an assemblage composed of tangible artefacts such as barbed wire, ditches (as visible in the picture below), bureaucratic regimes, and the tangible lived experiences of the different actors who cross it. To frame ‘the construction of physical barriers to transform a conflict line into an international border’, the European Union Monitoring Mission (EUMM), which has patrolled the Georgian-controlled side of the Abkhazian and South Ossetian contested border since 2008, coined the term borderisation.

Picture: Freshly dug ditch (near the village of Phakhuliani) – August 2022 © Gaëlle Le Pavic

However, the contested border is in some cases invisible – as in the landscape pictured below – yet its effects on the everyday life of differently situated individuals remain tangible. In my doctoral dissertation, I demonstrated how access to and the provision of social services are significantly affected for populations living on both sides of the divide. The Georgian population in the Gal/i district of Abkhazia is particularly at risk. Often disenfranchised, many have to cross the contested border regularly to access basic services and withdraw social benefits from ATMs located on the Georgian-controlled side. Medical crossings are frequent and in some cases part of daily life. A striking example is that of individuals undergoing methadone substitution treatment for opioid dependence – a treatment banned on the Abkhazian-controlled side. As a result, patients must cross the divide daily to receive their medication, navigating both physical and bureaucratic obstacles in the process. These examples illustrate how even when the contested border may be invisible in some places, it remains deeply felt, lived, and negotiated in the rhythms of everyday life.

Picture: On the brink of the contested border (the surroundings of Lia) – August 2022 © Gaëlle Le Pavic

Experiences of crossing the contested border vary significantly depending on one’s documents and ethnicity. For most Georgians, crossing into Abkhazian-controlled territory is not permitted by the Abkhazian authorities. Exceptions are sometimes made for those with family in Abkhazia, although such crossings have become increasingly restricted, particularly since the COVID-19 pandemic and Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine. For residents of Abkhazia, crossing into Georgian-controlled territory is also difficult. Several of my interviewees described ‘humiliating’ and ‘intimidating’ encounters with the representatives of the Abkhazian ‘State Security Services’. Exceptions to cross from the Abkhazian-controlled territory to the Georgian one are made for medical crossings, and some Georgian medical professionals are granted access to Abkhazia, especially HIV specialists, as infection rates are high within Abkhazia, including reportedly among the local authorities. Yet, those Georgians who do cross to Abkhazia typically face a triple checkpoint system: controls by the Georgian police, the Abkhaz authorities, and the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB) – and in reverse when crossing the other way.

The routines at the crossing points also differ: While accessing Abkhazia is today practically impossible for Western academics, the scholar Aude Merlin was able to cross in 2018 and experienced firsthand this multi-layered process at the main crossing point over the Enguri/Ingur River bridge – used by over 2,500 people daily on average, with important seasonal variations. In two hours of observation from the Georgian side on a Friday evening in October, 29, 2021 at the same crossing point, I witnessed only a few pedestrians and a truck, which changed registration plates before entering Georgian-controlled territory. The bridge (see photo below), originally built in 1941 by German prisoners of war, was deserted on that particular evening, as the crossing point was reportedly closed in the context of the Georgian legislative elections. Since 2017, only one other controlled crossing point has remained open, located away from the main road between the villages of Phakhuliani and Saberio and limited to pedestrian traffic only (see cover picture). Contrary to the Enguri/Ingur River bridge crossing point, this one is operated only by the Abkhazian authorities, without the presence of the Georgian police or the Russian FSB.

However, the remote location of this crossing point, close to road traffic, does not make for easier circulation. On the contrary, the assemblage of tangible and intangible mechanisms makes life difficult for the individuals whose daily routines span both sides of the divide. These constraints have intensified since the arrival of the Russian FSB in 2012, drastically reducing the informal practices and local arrangements that once helped ease the practical burdens of separation. What used to be a continuous space with no barriers has become fragmented over the last three decades, leaving an entire generation with no possibility to meet up with an antagonised ‘other side’. The only remaining windows of opportunity for Abkhazians and Georgians to meet are exchanges organised by civil society organisations and international non-governmental organisations, often supported by international donors and organisations. Typically, these exchanges take place in third countries such as Turkey and Montenegro and have an online component. Despite being increasingly controlled in Abkhazia, social media remains one of the only spaces where individuals separated by this contested border can interact.

While collecting data in such an environment is becoming increasingly difficult, the Georgian side of this contested border remains accessible to researchers. In another blogpost, I delved into the challenges this kind of research presented. Collaborating with other actors, such as civil society and representatives of international organisations, has proved very valuable. Additionally, co-producing knowledge with researchers living in those contested spaces allows us to address research gaps that inevitably arise from a lack of access. Additionally, the polarisation of the conflict impacts(academic) publications, often marginalising scholars residing within these contested spaces, in this case, Abkhazia. These collaborations can ultimately mitigate extractivism in academic research, and help us go beyond the ‘do no harm’ approach widely endorsed in research ethics protocols.

Picture: The main ‘controlled crossing point’ over the Enguri River (Ingur in Abkhazian languages) – October 2021 © Gaëlle Le Pavic

Author

Gaëlle Le Pavic is an associate postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy at Ghent University and a fellow at the United Nations University – CRIS. Previously, she worked for several years in project management and international cooperation, and she also contributed as a researcher to various projects addressing the social dimensions of migration and the consequences of COVID-19 for migrants. Her current postdoctoral work focuses on migration in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with a particular emphasis on social support across different settings. She was awarded two post-doctoral fellowships at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography in Leipzig, Germany, the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and the KIU Viadrina University in Frankfurt Oder. Her research interests include migration, feminist approaches to geopolitics, and the analysis of knowledge production.

Gaëlle Le Pavic is an associate postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Social Work and Social Pedagogy at Ghent University and a fellow at the United Nations University – CRIS. Previously, she worked for several years in project management and international cooperation, and she also contributed as a researcher to various projects addressing the social dimensions of migration and the consequences of COVID-19 for migrants. Her current postdoctoral work focuses on migration in the context of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, with a particular emphasis on social support across different settings. She was awarded two post-doctoral fellowships at the Leibniz Institute for Regional Geography in Leipzig, Germany, the University of Fribourg, Switzerland, and the KIU Viadrina University in Frankfurt Oder. Her research interests include migration, feminist approaches to geopolitics, and the analysis of knowledge production.

Citation: Le Pavic, Gaëlle, In/visible Contested Border: Im/material Evolutions of the Georgian-Abkhazian Divide, KonKoop DataLab Blog, published online: 28/05/2025, https://konkoop.de/index.php/blog/datalab-blog-in-visible-contested-border-im-material-evolutions-of-the-georgian-abkhazian-divide